Reality Bites is a feature series focused on the relationships people have with food, what kinds of cooking they’re inspired and sustained by, and the ingredients and tools that help them along the way.

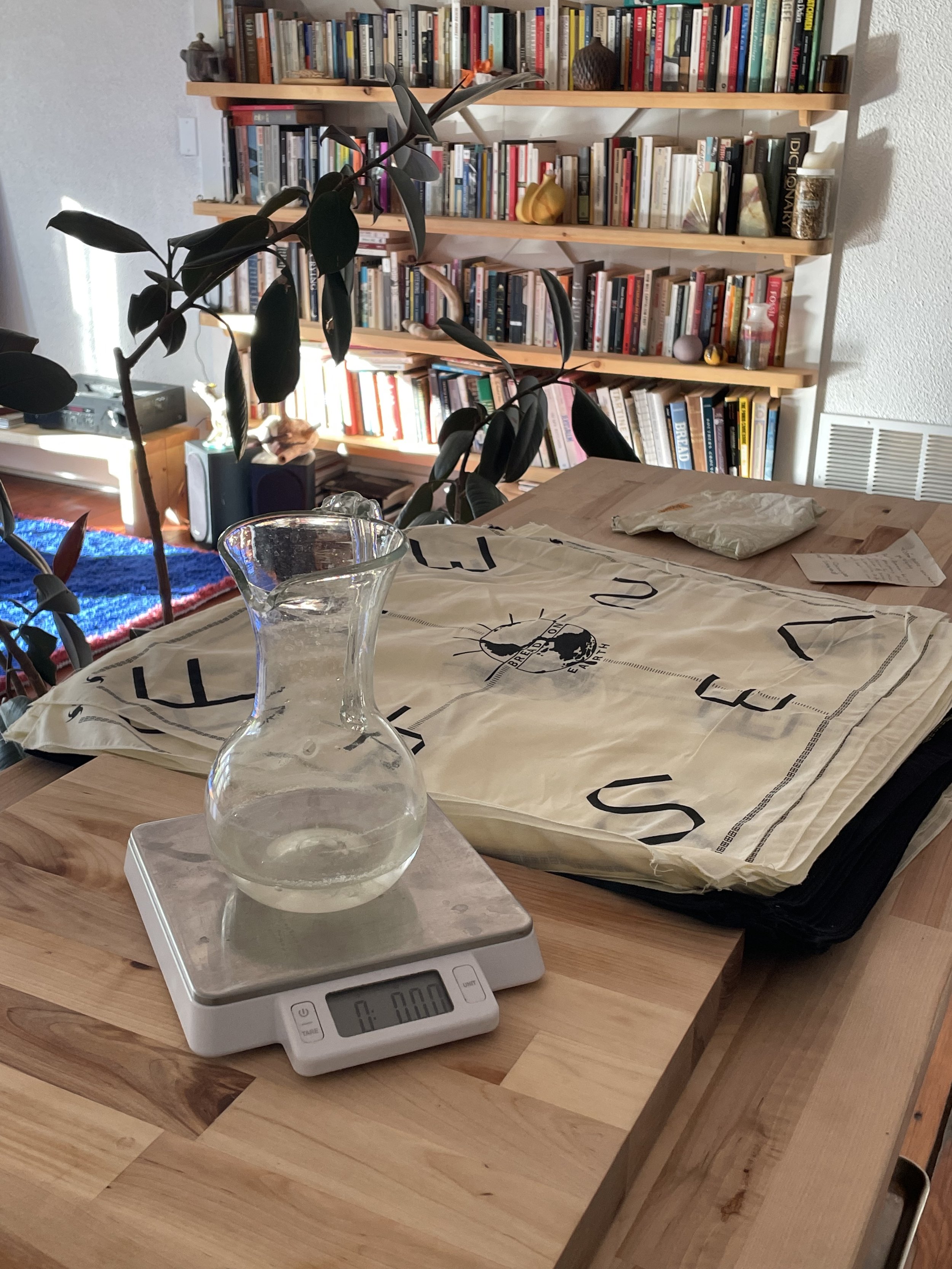

Lexie Smith is an artist and baker presently based in upstate New York who spends a lot of time researching, thinking about, and making bread. She runs the online resource center Bread on Earth, which explores bread’s “potential as a social, political, economic, and ecological barometer.” Through her early love of snacks and a penchant for going to cafes with her twin sister during adolescence in suburban New York, Lexie took an interest in food as a way of exercising control. These days, Lexie can be hard to spot as she’s usually in her studio in Ancramdale, NY, where the whole “downtown” consists of one intersection with a post office, a deli, and the studio building she shares with two other people. When she visits New York City, you might see her in the Periodicals Room at the Stephen Schwarzman branch of the NYPL, or playing with her son at Tompkins Square Park. Below, she shares her favorite spots for pastries, bagels, and loaves in New York City, as well as a variety of books and resources for learning more about bread and grains.

What is your morning routine like?

The real question is “what is my one year old’s morning routine like?” Every day rolls out according to his circadian rhythm. I stay in bed as late as possible, depending on what grace he grants me, which is usually not past 7 a.m. My boyfriend travels a lot, so when he is gone, it is just me and the baby, and we play and eat breakfast until our heaven-sent childcare arrives a few hours later. When my boyfriend is home, we split the mornings. I take the first shift and he takes over an hour or two later. After my baby time, I am often eating toast and occasionally drinking some decaf (quitting coffee is a big part of why I can get up at any hour necessary for the kiddo), and spending some time alone in the back room in our house, which has heated floors. An ultimate luxury. A lot of the time I will literally just lie there with my palms up and eyes closed — a deeply reclined meditation if you will. With a baby around, it is a treat to just be in a quiet room alone for a few minutes. This sort of day is kind of a rarity, though. I’m usually getting myself together (the only real priority is moisturizing my face, which I’ve done religiously since I was 13). I recently left a job I’d had for two years so my mornings now feel more and less pressurized at once — so much to do! So much to make of myself! No one asking for it! Pretty soon I’m packing my bag — the designer Adam Wade Wagner just offered to make me one to lug my computer and books and things to and fro and I’m kvelling — kissing my boys goodbye and heading to my studio.

Tell us a little bit about your background. Where does your interest in food in general stem from? What catalyzed your specific interest in bread as a medium?

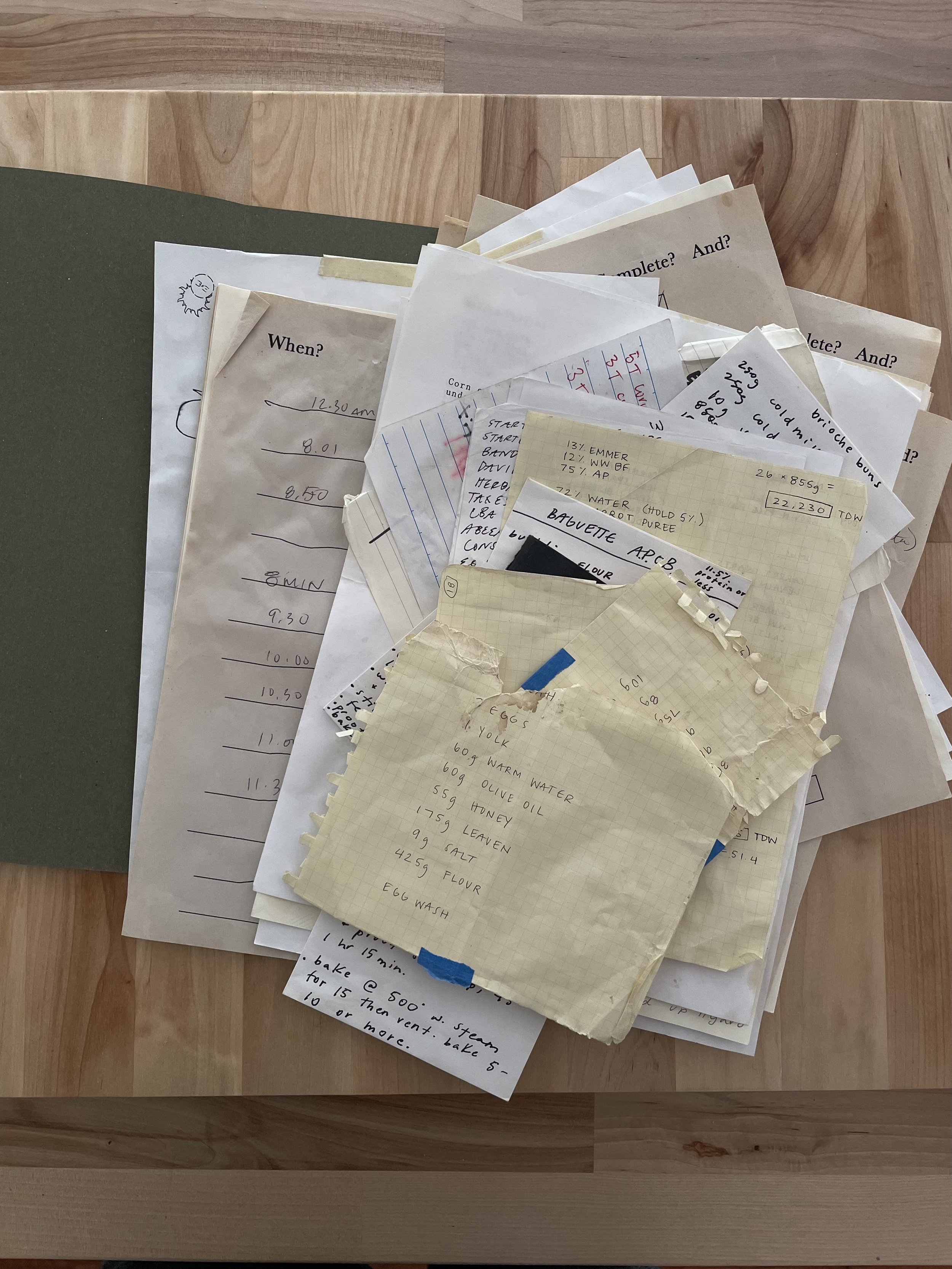

There is no distinct pinpoint, but I can say that food is the way that I’ve ventured into everywhere else I didn’t feel invited. From a young age, I loved restaurants, and eating of course, but there was a particular moment when I decided I needed to be making food myself, and this coalesced with a time in my life — adolescence — where I was feeling very isolated and generally disconsolate. I started messing with oatmeal and compotes initially, which snowballed quickly into baked things. I wanted control over something, and as a minor living under my parent’s roof, this was a grasping toward that feeling. From the very beginning, I was writing my own recipes, which is probably why I had what seems, at least to me, like a disproportionate amount of failures to successes for some time. The recipes were always a wily and creative act for me. Before I was baking, I was writing. I was like a tiny Jewish Sylvia Plath, totally obsessed with my notebooks. So realizing there was language that made food was exciting to me.

I was drawn to bread immediately when I got into baking. The alchemical nature of it, the invisible and mercurial inner workings, the subtle and overt responses to environment and handling, the wholeness of the product in the end, the humility of it, the reverence and also its eventual dissolution — the contrary thingness of it — it is easy to get hooked. It was clearly so human, and I could kind of control it. I started baking when I was a teenager, so by the time I was in my twenties in New York City and surrounded by self-proclaimed artists, I felt no entitlement — or access — to any other medium.

What is your earliest food memory?

My grandmother was a terrible cook, and I was a bit scared of her in general, but she made this dry crumbly carrot cake that I remember loving, even though I think I knew back then it wasn’t as delicious as it was supposed to be. She made it in a fluted pan, or at least in my memory she did. And the edges would get crisp and crunchy. No frosting. She kept desiccated orange zest in a small glass vial on the crowded counter and I always associated it with the cake, though I’m not sure if they had anything to do with one another. Maybe it’s just that they were both orange. I don’t know if I loved her but I really liked this cake.

What did you eat growing up, and how did it influence your taste?

I think that how I ate has affected me more than what I ate. I grew up in a pretty classic suburban household just outside of New York City in the ‘90s. We weren’t the house with the canned soda in the fridge but we did have a drawer full of snacks like Triscuits and Famous Amos cookies, and these were very important to me. I love a snack. My twin sister and I were skinny little things and no amount of junk food or ice cream, which we consumed enthusiastically, did much to change this. We spent a lot of time at friends’ houses eating their snacks too, memorably a friend’s parents who both worked in Manhattan would bring home large dark loaves of crusty bread (thinking about it now, I feel like it was a real classic Sullivan Street Bakery kind of loaf — I’ll have to ask them) and leave them propped up, cut-side down on the butcher block cutting board with a saucer of salted olive oil and balsamic next to it. It would stay there for days getting stale but would still be worth eating. This was the most romantic thing in the world to me, and I must have folded it into some part of my psyche that survived puberty because this scene now makes an appearance in my own kitchen with regularity.

I grew up as a totally a-religious New York Jew (recused myself from a bat mitzvah under the rationale that I didn’t believe in God and they were too expensive), with this part of my identity being entirely cultural as opposed to spiritual. Bagels, lox, and a “rustic” mirepoix do feel like home, even if I don’t eat them much. But — I’m sorry, mother — I wasn’t really interested in what I was eating at home unless I made it myself, and even then it was more an interest in process than flavor. I was curious about restaurants (where I would reliably ruin my dinner on the bread bowl) and the transcendent, fantastical quality they brought into a normal, perfectly nice world that felt otherwise bland. My sister and I had real love affairs with cafes. There were three in particular that are, like that bread loaf, inscribed somewhere in my DNA. Thomas’s, a tiny spot in our hometown owned by an elderly Chinese woman named Theresa and her son, the eponymous Thomas, where we would get cranberry scones and mango smoothies and Chinese chicken noodle salads. There was Caffe Reggio, still standing on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village, which we discovered at 15 and was probably 90% of the reason we moved to Manhattan. And Caffe Latte, a little Italian cafe one town over that my sister and I would walk more than an hour both ways to get to (we never learned how to drive, I just got my license at 32), all so we could sit amongst these old Italian men drinking their espressos and watching something on their little television while the lights from the pastry case glowed the place up. We’d get coffee and share a slice of the Frutti di Bosco tart. My Proustian moments take me to these places more than any others.

How is nutrition and food, for you, related to community, culture, and ancestry?

I think nutrition is much more than the nutrient density of your food. It’s whether or not what you eat makes you feel whole and comfortable and known to yourself. It’s whether or not it makes it easier or harder for you to get up in the morning. These things can be the result of community and culture or can build them. I don’t feel much of a relationship to my ancestral cuisine. The food that feels important to me is what I have made the most for the people I love, what I have seen bring the people I love the most joy and sustenance. This is what I will keep making.

You’ve resisted the term “bread artist.” Can you share why?

A painter is not a paint artist and conversely a “clay artist” is actually a potter. So why not just a baker? Or an artist? I think people who make food in such a manner that encourages other people to call it art should just be called what anyone else doing that with a different medium would be. Also, while I have an art and research project that’s focused on bread, it’s not the extent of my creative practice. The term ends up feeling like a caricature to me.

What was the process of aggregating the resource library on the Bread on Earth website?

Totally random. I put things on there that I found useful, surprising, and enlightening. I haven’t added to it in a long time but keep meaning to (a website overhaul is on the horizon!). I do a lot of online research, prioritizing free and open-source academic resources as well as snippets from books and literature that I can scan and share, which ensures that no one will confront a paywall. Because bread is so broad in its symbolism, significance, and history, I can scour all kinds of specialized databases using keywords and often come up with interesting new resources. I also still have access to my 14-year-old college login, which grants me access to databases like JSTOR, which I take good advantage of. I also always, always, read the footnotes and bibliographies and follow the trail of crumbs.

Where do you think the vilification of bread stems from?

It’s important to note that bread is really only vilified in wealthy Western cultures, which do not depend on it as a staple food. In these cultures — the Global North, really — the vilification began around the time of industrialization, when housewives were encouraged to stop baking bread at home in favor of a sanitized and mass produced product. This was the result of a number of campaigns, but only two are needed to get a clear picture. Xenophobia (many of the bakers making bread in smaller-scale bakeries in urban environments were immigrants), and profit (with the advent of hybridized wheats and steel roller milling, bread ingredients were being fine-tuned for mass production — cheap for the consumer and wildly profitable for the producers). Importantly, at some point the hybridized wheat developed for distribution across the Global South (with an intent to both feed and control the peasantry, ultimately succeeding at neither), has higher gluten and protein, making it a good fit for industrial growing and processing. This is harder for our bodies to break down, especially when coupled with the faster baking times and eschewing of fermentation, which begins the process of digestion for us, making bread much easier on our systems, in favor of more “efficient” baking productions. The rise in Celiac disease and preferences for gluten-free lifestyles is not entirely a fad or fantasy. But it’s not bread we’re allergic to, it’s (the often male-driven) greed for power and capital.

What are your favorite cafes, restaurants, bakeries, and local food makers? Where do you get takeout?

Takeout where I live comes from just a handful of restaurants a thirty-plus minute drive away, which I appreciate not because they’re too delicious but because they’re there and it means that once in a while we don’t have to feed ourselves. Sparrowbush is my favorite bread in the Hudson Valley — stone-milled flour ground onsite, a wood fire oven and a bunch of sweethearts. When I’m in the city, I spend a lot of time eating croissants. I don’t hunt down the best in the city exactly, I just get what is good and relatively convenient. When I’m there I stay in the East Village, so most of my spots are nearby at this point. C&B is a go-to not just for baked things but for a more wholesome breakfast or lunch, which you can take to Tompkins Square Park and feed to the squirrels. They have good, buttery croissants that fill the stomach and a bunch of other breads and pastries that I enjoy because they taste like they were really made to make you feel good. Lafayette has a good plain croissant but all the other viennoiserie there is an embarrassment of riches and the internet-inspired line outside is ridiculous. But it’s good for early weekdays. Tip the counter person. Il Buco Alimentari has a little sleeper pastry case with an excellent scone. And while I hate to jump on bandwagons, La Cabra makes a pristine — if not a bit tidy for my taste — plain and chocolate croissant, and an impeccable Danish seeded rye bread on the weekends, which I will wait in line for. Another bandwagon I’m sorry to say I’ve joined is for L'Appartement 4F in Brooklyn Heights, which is near my in-laws and makes a very delicious chocolate croissant.

For bread, an absolute must is ACQ Bread — make sure they are open before you go or find them at the Carroll Gardens Greenmarket. Try absolutely everything and give thanks to Tyler, the big-hearted mastermind behind it while you’re there. Arcade Bakery was an old favorite helmed by baker Roger Gural (they’ve closed, much to many of our chagrins, and Frenchette Bakery has taken their old location; they do pretty well in their own right). One of their bakers, Amadou Ly, recently opened ALF Bakery in Chelsea Market. I’m very anxious to try their baked goods, especially the laminated baguette which is a descendant of a favorite at Arcade. She Wolf at the Greenmarkets and found in Andrew Tarlow’s restaurants is an old standby for good bread, as is Lost Bread Co., based in Philly but selling at the Greenmarkets, to our good fortune. The latter also has delicious and insightful baked goods. For good flatbreads of all kinds (roti, taboon bread, pita, paratha, etc.) head to Al Aqsa in Bay Ridge or some of the other Palestinian restaurants nearby, Cafe Himalaya in the East Village for everything but also the paratha, or most of the roti shops you can find in Richmond Hill, Queens (this list could be longer and more precise but I think of flatbreads more in terms of neighborhoods than places, which I regret in moments like this). And Bagel Bunny is a popup that makes very special little bagels raised with a Japanese-style wild-fermented vegetable yeast. One-of-a-kind catering and food installations or just a plain old transcendent and life-affirming cake: Jen Monroe/Bad Taste Biz.

Essential cookbooks? Or resources for learning more about the history of bread and grains?

I learn most about the history of bread and grains from books without recipes, but cookbooks are essential to learning about bread because what you really need to understand it is to get your hands in the dough. So I recommend getting into both — they enrich each other.

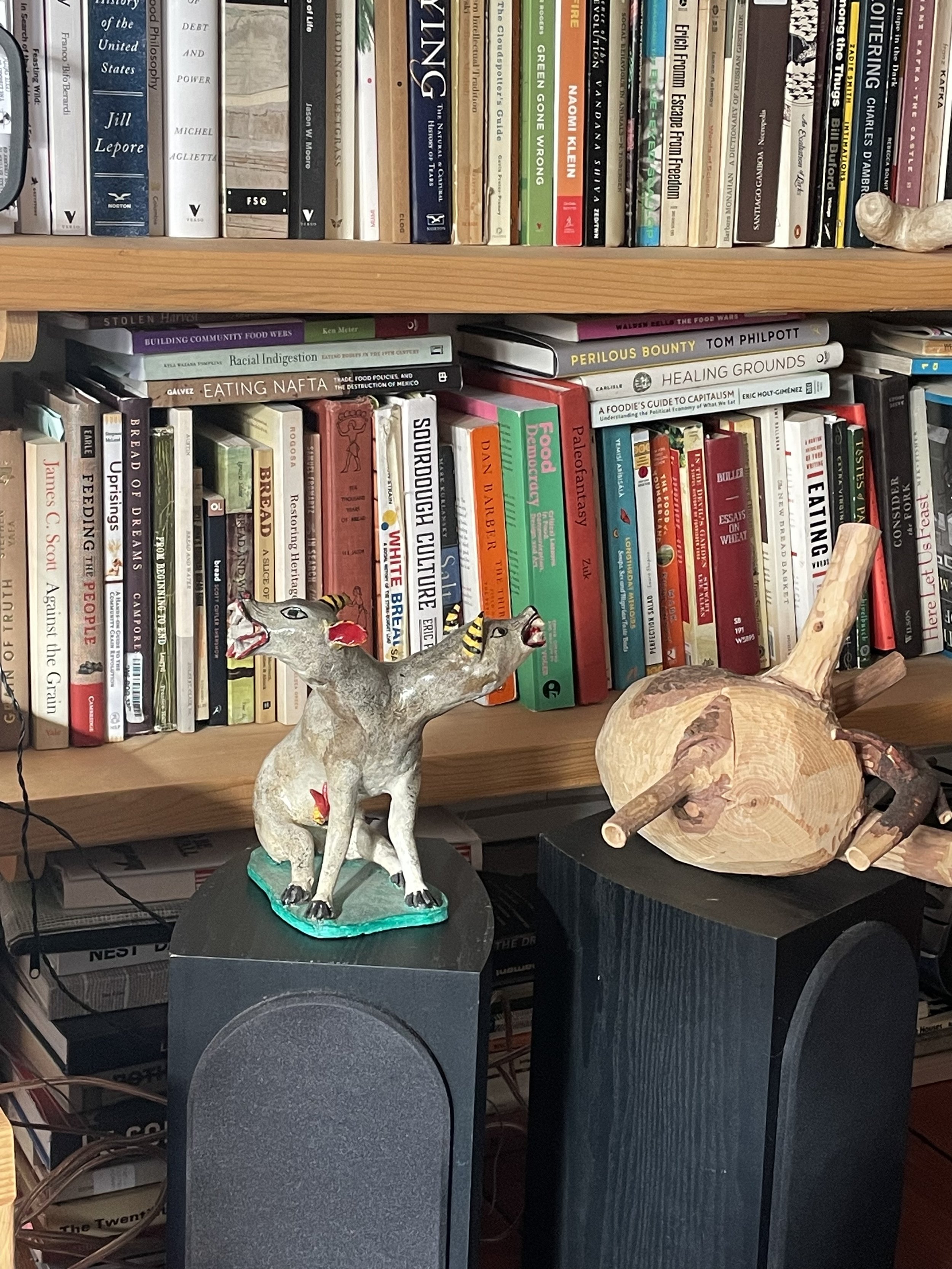

For non-cookbooks: Against the Grain by James C. Scott, White Bread by Aaron Bobrow Strain, Object Lessons’ Bread by Scott Cutler Shershow, Your Daily Bread by Doris Grant, and Bread of Dreams by Piero Camporesi are good places to start. For the more theoretical, scientific, obscure and/or nitty-gritty, there are tons of articles to be found on academic and open-source databases, some of which I have (illegally!) linked in the reference library on my website (to be updated tout suite).

For cookbooks: Read everything you can get your hands on. Jeffrey Hamelman’s Bread is thoughtfully and clearly written and gives a wide context and strong foundation on which to build. The Bread Baker’s Apprentice by Peter Reinhart was a good starter course for me back in the day. Of course people love the Tartine cookbooks — they’re inspiring in their recipe proportions and baking style. Chad Robertson really championed the very wet — high-hydration — dough a lot of people are looking to make these days, but I don’t find the recipes incredibly reliable, especially for a new baker. The Perfect Loaf is a newer addition to the canon but widely beloved for its consistency, specificity and relative simplicity. I recently got Bread Head by Greg Wade and while he leans a little (a lot) heavy on the Grateful Dead references, I think the recipes are fun. I love the Nordic Baking Book by Magnus Nilsson, a brick of a book that I have permanently stolen from my friend Georgia Hilmer who lent it to me full well knowing this was a likely outcome — it is full of obscure and tantalizing regionally-specific baked things.

And lastly, don’t underestimate the power of online amateur forums. I know we live in a different world than when I was starting out (ahem, TikTok), but during my early days of bread baking, I learned an incredible amount on forums like The Fresh Loaf from the other non-professionals who were just trying to figure out what the hell had gone wrong. Many of the posters there have been going strong for well over a decade, and have learned a lot in that time.

Who are your dream dinner guests?

My twin sister, her husband, my boyfriend, and a couple of good friends. Big meals make me nervous. I like to eat at a round table, not too big, with people I’ve known for a long time. Fran Lebowitz would be fun though.

all images provided by lexie smith, edited by sammy case