Camera Roll is an interview series where we glimpse into the current moment via the mundane and the ordinary — the life documented and forgotten, lived through our phones and beyond.

You might not be able to spot filmmaker Amandine Gay — when she’s working, she spends her days at her desk, and she’s often working. She is the creative force behind Speak Up, a documentary that highlights the stories of Black Francophone women, and A Story of One’s Own, an archival documentary about transracial and transnational adoption. She’s also written a book and is at work on another, she’s a frequent speaker on filmmaking, feminism, and adoption, and she has her own production company. But she might spot you when she’s taking a well-deserved break people-watching in Montreal’s cafés. We spoke to Amandine about developing an Afro-feminist aesthetic, sleeping in on the weekends, and getting a hysterectomy.

What kind of phone do you have and how many images are on it?

I have an iPhone 11. There are 3,638 photos and 387 videos on it.

When did you get your first phone, and what do you remember about it?

It was near the end of French high school, so I was 16. All I remember is how happy and relieved I was to no longer have to deal with prepaid public phone cards, never-ending waiting at the bus stop, or very long walks because I couldn’t ask anybody to pick me up. I also remember playing Snake obsessively!

How long do you typically spend on your phone in a day?

I don’t keep track, but it depends on the type of day. If I’m writing, prepping, or shooting, I don’t spend much time on the phone. Usually, during breaks, lunch, or after the work day I’ll do a few checks of my emails and WhatsApp to make sure there are no emergencies. If I’m on tour promoting my work, I will spend A LOT of time on the phone because I manage all my social media myself. If I’m on holiday (which is sadly rare), I spend as little time as I can on the phone and usually put it on airplane mode during the day so that I won’t be disturbed.

Where are passersby likely to spot you? What are you doing there?

When I’m writing, especially on a deadline, no one’s likely to spot me, as I spend most of my days at home in front of my desk. When my work schedule is more relaxed, I love to stand at high tables on the windowsills of Montreal’s cafés, chasing the light, since Montreal’s winter is pretty intense. I’m usually working on my computer, or I’m enjoying a well-deserved break, drinking an almond chaï latte while gazing at people walking by (one of my favorite activities in life). Otherwise, they might see me running on La Piste des Carrières in Montreal, when the weather permits it, or on L’ Île Saint-Denis when I’m in France. I also spend a lot of time at a studio in Montreal’s city center where I practice Hot Pilates, Hot Yoga, Hot Barre, and HIIT.

Where are you right now?

I’m in Saint-Denis, France, for work. In my apartment.

What's your morning routine like?

I wake up naturally, no alarm clock. I like to be up really early. It’s my favorite part of the day. It feels special, the energy is so focused and quiet. This isn’t ideal but I go straight to email. Since I work with Italy, I like to catch them as early as possible before their EOD. Then I start to get ready, putting all the cold things on my face. I can’t start my day without this part. What else? I almost always forget to drink water.

what do your days look like?

On weekdays, I wake up between 6:00 and 7:30 am. First up is meditation, yoga, or a warm-up routine, or running in the spring and summer. Between 7:00 and 8:30 am, I have breakfast, and for the rest of the morning I do admin (emails, social media) and if I’m in Montreal I might have calls with Europe. In the fall and winter, I train from 12:00 to 1 pm — either Hot Pilates, Hot Yoga, Hot Barre, or HIIT. At 1.30 pm, I have my lunch break.

What was your upbringing like as a transracial adoptee in the French countryside? can you tell us how you got to where you are now?

I was born in 1984 under a law in France that allows women to give birth anonymously. I was then adopted by a white family living in the countryside near Lyon. I had no information on my birth parents, so it made the recurring question “where are you from?” an even more problematic one to me. Not only was I constantly reminded that I didn’t fit the norm, but I didn’t have any outside relations either.

In France, in the 1980s-90s, the only Black people on TV were on American shows, like The Cosby Show, Different Strokes, and The A-Team. There were also Black American stars like Whoopi Goldberg, Whitney Houston, etc. — it did make me feel good seeing them on the screen but that wasn’t enough to make me feel like I was a member of Black communities.

In retrospect, I’d say that my reality growing up was one of isolation and underrepresentation in public space and in the film and TV industry. The depoliticized or caricatured narratives of the lives of Black people, queer people, or adoptees fed my yearning for symbolic reparations. My artistic and advocacy work is completely entangled with my personal history. It’s through creation and activism that I have been able to make sense of my situation and reclaim my many othering identities: transracial adoptee and bi/pansexual Black woman.

As an adult, I’ve found agency by creating from the margins and developing an Afro-feminist aesthetic, but I’ve also realized that I need a sanctuary to keep working on issues close to home, with (often) vulnerable participants — which leads me to Montreal, an extremely diverse, green, and queer city, where people are chill. I was missing the benefits I got from nature, which I experienced growing up in the countryside, but I could never be in a small village or town ever again. I like the freedom in this city. Maybe it’s confirmation bias related to my entourage, but I feel that queer people are the majority in Montreal, which is great for me!

How did you first get into film? what about documentary film makes it feel like the right medium for you?

I’ve chosen cinema & TV because they give agency to unheard or less-heard voices and help us flip the script and reclaim the narrative through the power of the moving image. Films have allowed me to visually translate the motto “the personal is political”, recording, compiling, and shaping individual experiences into a collective narrative.

My first feature, Speak Up — a two-hour film almost entirely composed of close-up interviews shot with a handheld camera in natural light — was about pushing the boundaries of the “talking heads” documentary. It was my way of placing Afropean francophone women at the center of the narrative, both politically and visually, filling the frame with their faces, hearing their voices, showing their common identity and the subtlety of their specific experiences. For my second feature, A Story of One’s Own, I chose to explore another documentary genre — the archival film — once again trying to find the form that can best suit the narrative.

My approach as an indie producer-director can be summarized as follows: to tell, document, and preserve the stories and contemporary realities of those who are usually absent from history — Black women, adoptees, or members of any other minority and invisible groups. I believe that unscripted formats are as powerful as scripted ones, especially if we choose to make them aesthetically daring and politically challenging.

How do you strike a balance between work, activism, and free time?

I’d say that I’m getting better at putting the need to sleep and rest first, which means that I had a long list of things to accomplish during this weekend, but I’ve learnt to accept that they won’t all get done and it’s okay. I’d rather be late than exhausted, as I used to be. I’ve worked all weekend, doing pre-interviews and dealing with things development for a docuseries I’m working on prevented me from doing during the week, but I slept late yesterday and today, and even went running before lunch today.

I feel like I’m constantly researching as I love watching films and series and going to exhibitions, plays, and any type of performance. I’m also often participating in workshops as a producer, filmmaker, and performer, so I’m learning a lot from other people, which I consider research too.

I’m not politically active when I’m heavily invested in creation. I’m hyper-sensitive and anxious so if I get too close to the news, I slip into depression and get stuck. As I grow older, my activism is more and more expressed through my creative work (for instance, my next book is about white supremacy as a political regime) and less through organizing, as my availability and energy is not the same as it was a few years back.

what’s been inspiring you?

Saul Williams, Lynnée Denise, Karim Kattan, and Maya Mihindou. They always seem to find a way to address the chaos we live in — starting with the situation in Gaza — in a powerful, clear-headed and empathetic way. Their presence in the current public and artistic sphere has been crucial for my sanity.

any advice for those who want to be filmmakers?

I’ll share what I wish I’d been told:

Don’t compare yourself to anyone, especially if you’re a Black queer woman from a rural working-class family. It takes time that it takes, but with stamina, hard work, talent, and grit, you’re gonna get there. There being, for me, the joy (and gratitude) of traveling around the world, constantly meeting new people, having the opportunity to impact people’s lives, and being able to work in my pajamas all day — and watch movies in said pajamas knowing that counts as work too!

Make sure you love the work. What’s kept me going so far is loving what I do. If you’re choosing filmmaking because you need to be covered in laurels, awards, and whatnot, spare yourself the trouble. The recognition and free champagne at festivals are cool, but let’s be clear, the satisfaction is in creation and true self-love comes from therapy.

This is an industry, you are an entrepreneur, and you need a career plan. Strategic planning changed my life by allowing me to set realistic objectives: where do I wanna be in a year, two, five, etc. You need a team. I’ve only had a manager, a literary agent, and a film/TV agent for a year, and it’s made my life so much better, as it opened so much more time for creation. You need money to get to the next steps. It took me five years to realize that indie documentary filmmaking was NOT the way to earn a living. Television is. Find gigs that pay — and make sense to you — so that you can work on your darling projects. You’re welcome!

Sleep. “They sleep we grind” culture is the most toxic and stupid sh*t I’ve ever heard. We’re not here to serve capitalism, we’re human beings — artists. I sleep eight hours a night, at least. And if for some reason I don’t get that, I will sleep for ten to twelve hours a night on the weekend.

I was so right to get a hysterectomy! Being child-free (and period-free since 2020) makes my life as a filmmaker very easy. If you want children that’s cool, but I know that many get pressured to become parents, and let me tell you, I’m extremely fulfilled having chosen not to. Remember, it’s a choice.

You’ve talked about the importance of archives and about the lack of archives documenting the lives and work of Black women. Are there archival materials that have been particularly important for your work?

Film archives at the Forum des Images and Bibliothèque Nationale de France have been extremely important to my study of the French colonial past. In France, we’re also super lucky to have l’INA (the National Audiovisual Institute) which catalogs, archives, and sells all types of archives from cinema and TV dating back to the beginning of these mediums. It’s been the main source of historical archives for my second film, A Story of One’s Own. More recently, I’ve loved discovering an array of black films I had never even heard of thanks to Maya Cade’s amazing work at The Black Film Archive.

What are the references you return to in your filmmaking? are there particular artistic and/or intellectual movements you see your work as in conversation with?

I don’t have “fixed” references. An array of films and directors have made an impression on me, so depending on the project I embark on, I go back to different artists or works of art. For instance, when I decided to make A Story of One’s Own, my references were archival films with no talking heads, using only images from the archives, especially ones with a strong political stance or a very intimate approach. For instance:

Concerning Violence by Göran Hugo Olsson is a documentary which (except for its prologue) is made up entirely of Swedish television archives, interspersed with notable passages from Franz Fanon's Wretched of the Earth. The narrator is Lauryn Hill and everything from music to editing, right down to the titles of the sequences, contributes to its political and aesthetic statement.

Marta Popivoda’s Yugoslavia, How Ideology Moved Our Collective Body, which solely displays archival images, all in 4/3 format, without voice-over — or more precisely with the sole narration being that of the images and voices present in the selected archives. The film’s concept is to bring into dialogue the official mass demonstrations and the counterdemonstrations in Yugoslavia because as the title indicates, it is about representing the evolution of communist ideology through mass movements.

Autobiografia lui Nicolae Ceausescu by Andrei Ujică is a striking example of how it is possible to structure a narrative with a great economy of means – no commentary, no music, no chapters or explanatory texts. This film is a reference for me when it comes to the use of editing as the only narrative device.

Tarnation by Jonathan Caouette, who started documenting his hectic family life from the age of 11 through video, photo, and audio recordings. It’s a kind of an experimental film, and yet, it draws us as viewers into a whirlwind of images that allow us to grasp the impact of the director's mother's mental illness on his own construction of himself as a child and as an adult.

Another film that I found very inspiring in its creative use of archives is Je ne me souviens de rien (I Don't Remember Anything) by Diane Sara Bouzgarrou. In 2010, while going through an intense manic-depressive episode, she documented everything with her phone and a small DVCam, then forgot the rushes following her institutionalization and was reminded about them by her boyfriend 5 years later — which prompted her to turn them into a film. One has the sensation, when watching her film, of diving into the state the director was in when she shot these images. The strength of this film is its ability to make the viewer empathize with a situation that they have not experienced, thanks to this “never seen before” kind of archive.

How do you use your phone or other tools (like a journal, for example) to mark, store, and remember moments?

I used to make scrapbooks where I cut and pasted things collected during my travels. I still keep everything (transport tickets, brochures, etc.) but I no longer have the time to do anything with them so I accumulate physical archives that I might turn into an exhibition one day, just to force myself to do something with them. These days, my partner and I use the app BeReal to track where we’ve been and what we are doing, and then we print the photos and make albums that are kind of a photo journal of our lives.

I mostly document for work (promo, etc.) because my partner is a photographer and he’s the one taking photos of our private life. I realized that many photos on my phone are taken by him or my friends. I tend to document things by wanting to be in the picture, to remind myself where I was and with whom.

I only delete when I’m about to reach the storage limit!

What’s in your podcast queue?

Only things recommended by friends:

Lamin Fofana on NTS

This episode of Les Midis de Culture

Quelques raisons de ne pas disparaître by La Clameur

Moss Matters from Serpentine Podcast

Ruari Paterson-Achenbach’s Lesbian Families.

what are you watching?

I’m currently watching True Detective: Night Country (HBO), Criminal Record (Apple TV), Big Boys (Chanel 4), Grand Designs The Streets (Channel 4), Surgeons: Edge of Life (BBC), The Forsyte Saga (BBC).

What apps on your phone do you use most?

My favorites are:

FitOn: I love DeAndre’s meditations and yoga

Drinks Meter: an app to track one’s alcohol consumption — best lifestyle improvement of the past couple of years.

Health App: I have an Apple watch and I train a lot, so I like to check my progress/results, etc.

And I use Gmail, WhatsApp, and Instagram a lot.

favorite new possession over the past year?

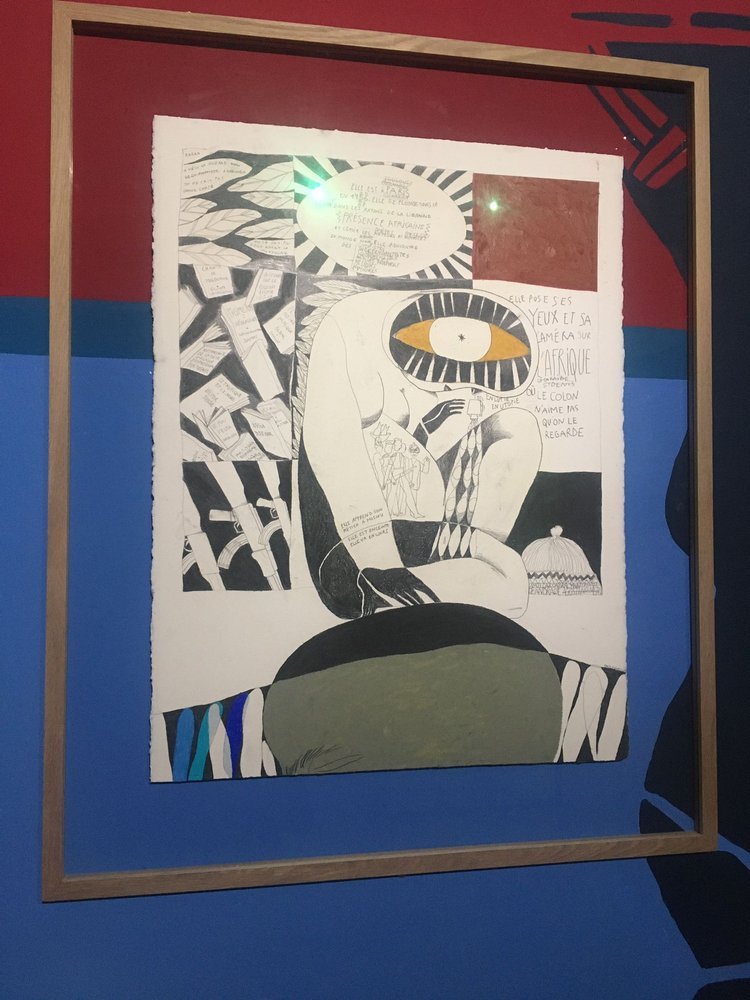

Three drawings from Maya Mihindou’s series on Sarah Maldoror.

last thing you googled on your phone?

“Adolescent tué saint denis” which means “adolescent killed in Saint-Denis” because there was friction between rival neighborhoods in my city in France last week and that resulted in two kids being killed. The first one was 14 and stabbed at the subway station and the second one was 18 and beaten up with baseball bats outside his high school. I knew about the first kid, but a neighbor told me that it escalated so I wanted to know what happened.

Can you describe your lock screen?

My lock screen is a picture taken by my niece when we visited Martinique last April. It was a sort of pilgrimage, since both my brother and I are adopted and from Martinique (even though we aren’t related). Our (adoptive) mother offered to finance a “back to the roots” trip for us. What I like about that picture is its irony. My partner and I are seen from the back, walking to a supermarket named “Caraibe Price”, which translates to “the cost of the Caribbean” in French and has a double meaning given the history of colonization and slavery that still scars the island to this day. We’re wearing shorts and the sun is shining through the clouds, but it sure is not paradise.

what is a memorable image on your camera roll, and what does it mean to you?

There’s a selfie I really like because I managed to get a “double rainbow” on a Montreal street. On the right-hand side of the picture, you have half of my sunlit face (covered by my hoodie, since it had just stopped raining), and in the left-hand corner, you have the road, clear of cars, and at the far end of it, the rainbow and its reflection.

images provided by amandine gay, edited by meghan racklin