Writer and professor McKenzie Wark might be reading a book if you spot her in transit on the NYC subway, but she’s more likely to be on her phone, reading (or composing) an incisive Tweet. This proclivity is indicative of the dichotomies McKenzie frequently breaks down with her work: labor versus play, a day job in academia versus nightlife at queer raves, authoring acclaimed works of cultural criticism versus 280 characters tapped into a cell phone while waiting for the L train… McKenzie invited us into her new, not-quite-unpacked apartment to speak about her punk-soundtracked pathway to academia, rave strategies to keep you on the floor no matter your age or the hour of the day, and the manual labor being a writer entails.

♫ Listen to mckenzie’s playlist | ⌨ mckenzie’s last google search

on her morning routine

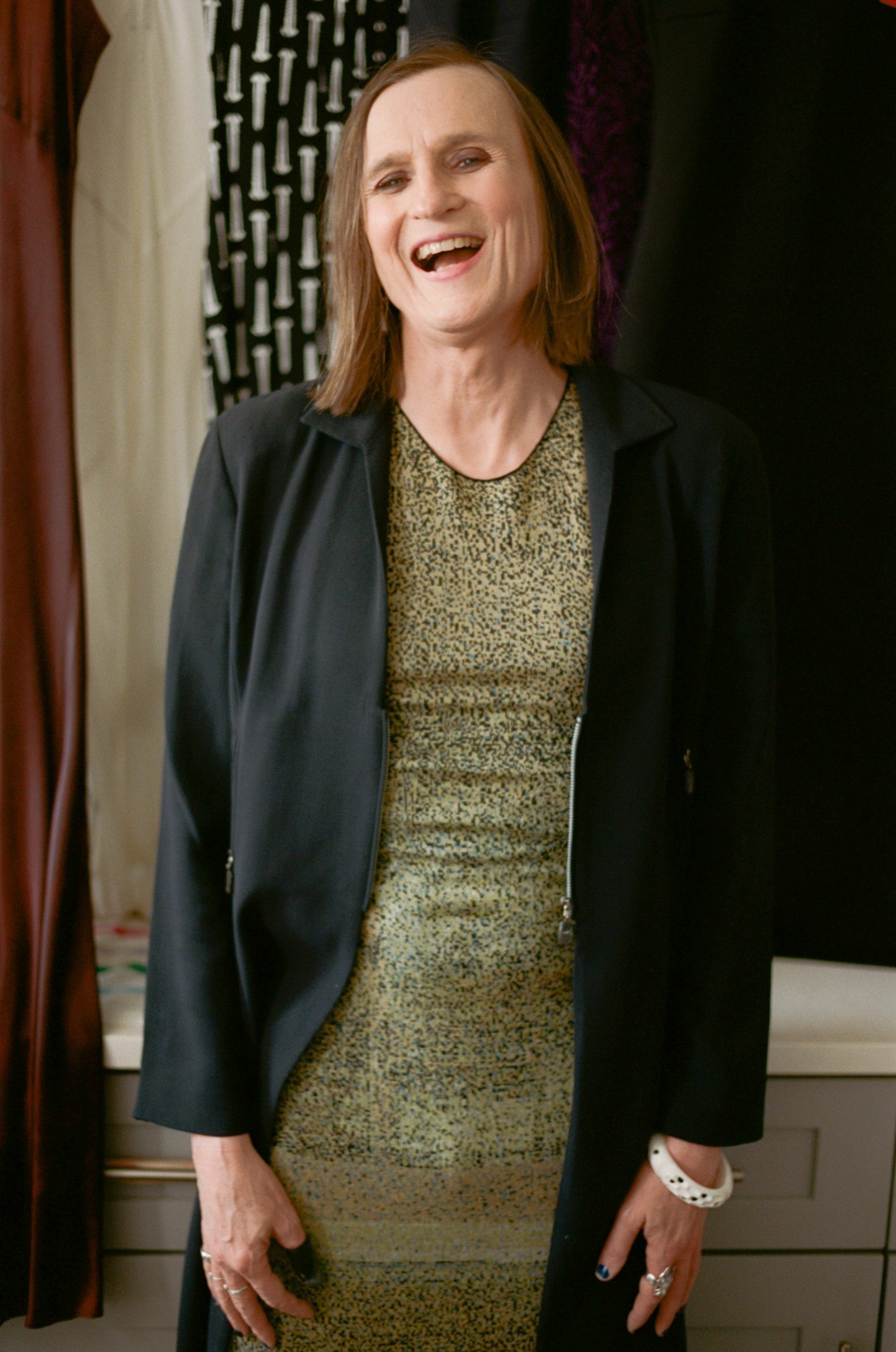

I have two cups of Earl Grey every morning if I’m going to deal with absolutely anything else that day. Then, I trawl the internet — I'm addicted to Twitter, I need to see what all my girls are doing. Breakfast is blueberries, unsalted pistachios, unsweetened liquid yogurt, and a dash of maple syrup. I get dressed and download the SoundCloud mix I’ll listen to that day so it’ll still play while I’m on the subway. I follow a few local DJs and just pick a tempo for the morning. If I'm going to work, I wear the same thing over and over again: Stuart Weitzman 5050 boots, little skirts, and tights when the weather is cold.

on growing up in, then leaving, australia

I had a provincial, middle-class childhood in Australia. My father was an architect, my mom died when I was six. I was substantially raised by my older brother and sister whom I thought were adults in charge of me — they were still in their teens. As my co-parent says, I was raised by wolves, but they really loved me and did an excellent job, all things considered. I left my hometown young, and as a teenager, I lived in Sydney for a long time, where I ran a bit wild. In the mid-90s, I met a New Yorker, fell in love, and emigrated. I was a “public intellectual” in Australia, I had a newspaper column, and I was writing books that were angled toward our national culture, but I threw away my Australian career and started over. I came to American academia too late to really figure it out, but I found a job at the New School and got to build a life in New York!

on the punk roots of her career in writing and academia

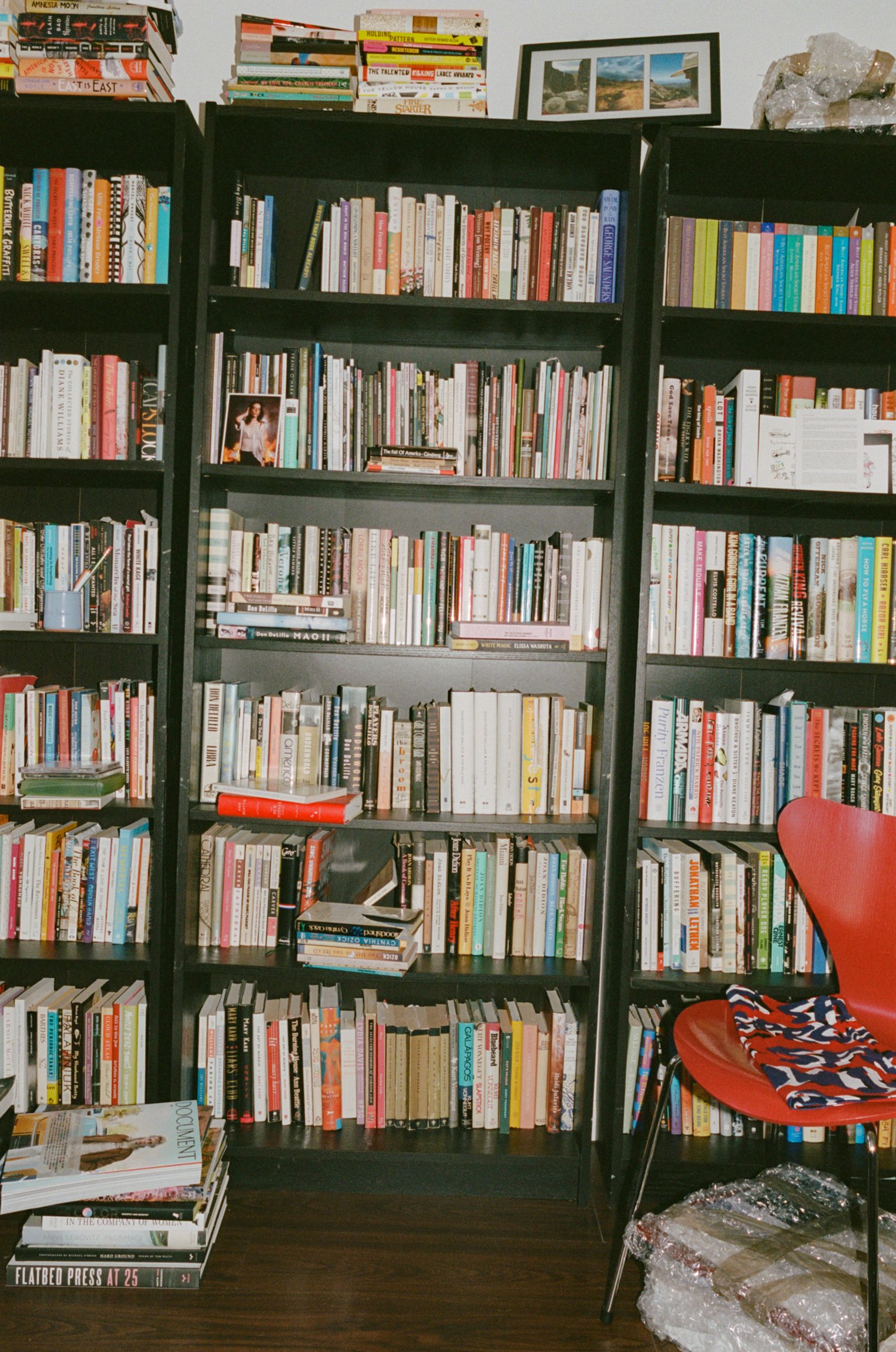

My attraction to Critical Theory and academia can be traced back to being a teenager in the mid-to-late-70s, in the punk rock moment that was very much about DIY culture. I came to writing as a career because of my complete musical incompetence, even with three-chord punk rock, but I internalized the idea of the economy of that form, and how you can intervene in culture in a way that connects emotionally while protecting your niches at the same time. At that time, I was reading Guy DeBord and picking up references from New Musical Express or interviews with more erudite post-punk bands. If you're in the provinces, you're not in the center of culture, so we had to find alternatives. We made a lot of zines.

““Writing is the least collaborative art. I used to, and probably still, write in a very dissociated state. It’s a very solitary practice, but language is my only skill in the world. Obviously, I’m a talker, but this confidence was a survival mechanism thing in school. I was the runty little kid, suspected of being gay, so I had to be funny, entertaining, and tell stories. In Australia, we call it “the gift of the gab.” There are writers who don’t like to talk, and that’s why they write. My writing comes out of verbal instincts, and then it’s just a matter of putting it onto the screen.””

on tips for aspiring writers

Do a local open mic, find a form of community organizing that needs someone to be able to speak. So much of producing language is about listening, too — it took me a while to learn that. If you can sum up a discussion, coordinating all of the points of view in the most effective and articulate way, you’ll be able to write. There will always be quite strong opinions on what to argue, but the real art is weaving those threads into a consensus using language. It's been helpful for my writing to teach undergrads. If you can explain an idea to intelligent, interested 18 to 23-year-olds, you're onto something! That’s a problem in American academia — people want to work on the graduate side where everybody's trying to be smart and to have done all the readings, whereas undergrads haven't read the damn thing at all, half the time. You have to get them interested.

The rest of my life has suffered to make time for my teaching and writing. A lot of people think that they're writers, but they don't actually write. If you're a professional guitarist, you are picking that instrument up and playing it every day, but there are people who think they’re writers without practicing. You just have to be on the keyboard, banging away. Writing is just manual labor, there's no thinking involved. The thinking comes later. You just make the words — the secret sauce is the editing, the chopping, and reworking.

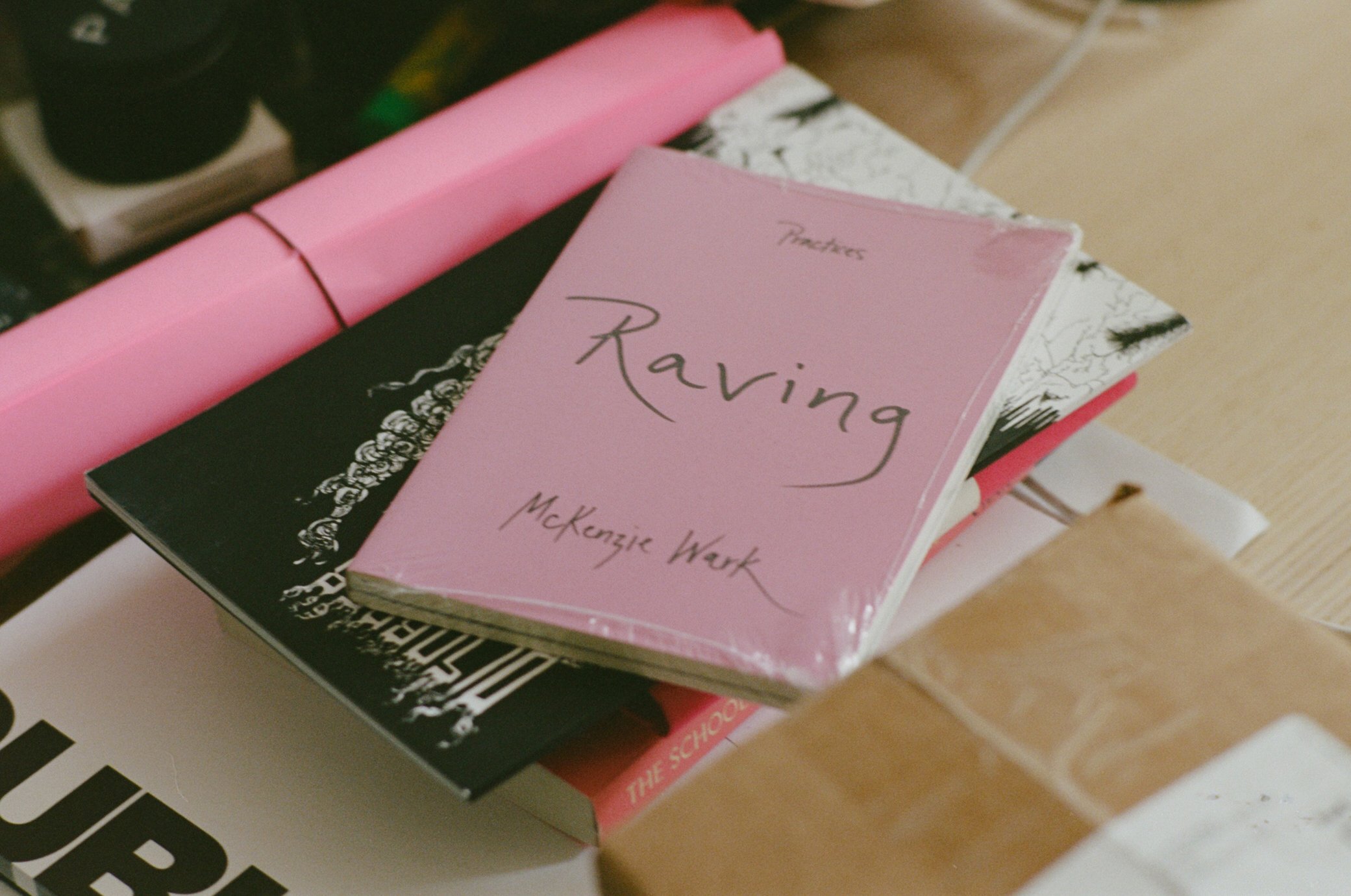

on rediscovering writing through raves

Being a 61-year-old raver in an American context is kind of hilarious. In Berlin, that would not be unusual! In New York, there are just a few other older people I see around. My first exposure to techno raves was in the 90s when I was married to a self-described “rock chick,” so we would usually go to rock shows instead. When I came out, my trans mom was a raver. I was just having one of those conversations you have with your trans mom about unending, low-level gender dysphoria that nothing works to combat, and I said “I only feel good when I'm dancing.” She was like, “You are coming with me, you will arrive at my apartment at two in the morning, and I will take you out,” so I was reintroduced to raves in my late 50s, after a 20-year gap.

When I was hormonally transitioning, I couldn't write for three years. That was a real crisis. Raving is where I found how to write again, and that was really liberating. I wrote a piece about someone I was attempting to date at the time, there is this really abject scene where we fuck at a party, and the next morning, she's like, “I don’t think we should do this anymore.” I was so crushed, but I just wrote that down. It's just gonna be a story, and concepts flow out of the stories. Writing about raving is a love letter to the scene. It let me in, so I want to document it, but also keep it a little bit invisible at the same time. The NYC queer and trans rave scene doesn't need tourists, it doesn't need people showing up to gawk. If you're trans, that happens to you all the time, and this is a place where our being there is ordinary, and that’s a relief. I want to keep it that way, but at the same time, I want to document the fact that the people I got to meet made something special because it won't last forever.

““At raves, we’re all working on producing nothing at all. I’ve never worked so fucking hard in my life as I do dancing, and all we’re producing is heat. Most people’s jobs probably harm something in the world, it’s unavoidable under capitalism, but to be working to produce nothing feels like blessed relief.””

on strategic raving and dance floor dos & don’ts

The secret to maintaining energy while raving is very simple. You go to bed early, and then you get up at four in the morning to be at the party by five. You can absolutely rave without taking drugs. A lot of people drink mate, which is very caffeinated — that'll keep you going and keep you hydrated. I think it's very important to say that there are whole networks of sober ravers in town.

A lot of straight guys have a hard time dancing. They won't let the music into their bodies, so they will generally barge their way through the crowd to the front of the DJ booth, beer can in hand, and do the damn fist pump thing three times. They take up space and then go away, and it's like Honey, just let it in. This doesn't mean you're gay. You might be a little queer on the dance floor if you let this happen… but no one's watching! You're not that interesting. The crowd eventually sorts out into people who want to dance for 20 minutes, often in a quite showy manner, and people who came to dance. There's a certain economy of movement in long-haul dancing that you learn through practice. In NYC, you can go to the club on a weeknight and just practice being on your feet.

The most ridiculous thing that’s ever happened to me at a rave was getting asked for a letter of recommendation on the dance floor. This is not office hours. I don't need to be fucking Professor Wark in this instant. I'm on drugs, I’m not wearing appropriate clothing, and I'm in my moment, you know? I probably ended up writing the letter of rec and never mentioned it again.

““To be able to dance, you have to let the music fuck you, and not everybody’s willing to let themselves get fucked. There are a lot of intimate relations you can have with the music, but you have to be open to them. If an aesthetic experience is worth anything, it puts pressure on language. I’ve had to find ways to describe queer nightlife, not necessarily in new language, but in different language. It’s not transcendence, it’s not resistance. It’s not utopia. It’s not church.””

on the intertwining of nightlife and her day job

I absolutely always have to be rested and sober before I teach. It's important to me that there is a boundary there. I taught a course on Nightlife last semester, which I've completely reworked to teach next year. At the New School, we get a lot of 18 to 22-year-olds who want to have the New York experience, but they grew up in the suburbs, and they go to really shitty clubs. 95% of theme have been harassed in nightlife, this includes a lot of cis man, bad stuff has happened to almost everyone. Sometimes they don't know basic stuff, like, always go with a friend, don't accept drugs from total strangers, if your friend is in trouble, you stay with them, if they go home with somebody makes sure you know who it was. There are clubs the students have heard about that are not necessarily any good, they're huge, and they don't really have staff paying attention. Or maybe the students are queer and going to straight clubs, wondering why they always have a terrible time. There's no such thing as a safe space in nightlife, but there are safer spaces. Where are they? How can you be a part of that? This found its way into my writing as well, like in my new book, Raving, but it's also a developing curriculum.

While I've had students come in who just didn't know how to enter nightlife, I've also had students write these knockout reports about what's going on in nightlife in other countries —for example, what a raid is like in Beijing. It sounds like a nightmare, they drug test everybody on the spot, 100 cops show up. Or students write about nightlife in Singapore, where all these party drugs are criminal offenses. There have always been students who have explained to me how culture works, these days, and there have always been students who needed to make work of some kind just to be viable as people in the world. I relate to that, so we share strategies for surviving as a human through some kind of creative practice, sometimes through collaboration, or just letting them show me how they work, and also how they live, a little bit.

““When I get dressed, I use conventional signs of femininity to help other people figure out how I want them to read me. This assumes people have goodwill. They’re like, ‘Whatever it is, it’s wearing a skirt, so I’m gonna go with “Can I help you, ma’m?”‘ I feel more comfortable helping other people out a little bit.”

”

on coming out as trans later in life

It's hard to talk to younger people about aging because it's the one thing where there's always this asymmetry of experience you can’t get over. I know my time is limited. Young people always want to tell me “You’re gonna live for a long time.” The time speeding-up thing is real. I’m really going to enjoy this time now, and not be neurotic and stress out about all the bullshit that used to bother me — that's the one blessing, I just so don't care. There are two kinds of trans people really: those who can hide it, and those who can't. And if you can't hide it, and you come out young, it's probably going to shorten your life, we all know that. If you can hide it, you might live a long time, but if you then come out late in your life, that version of you is short-lived. I get to be this for a very brief period of time.

It was harder to figure out any of this because there wasn't access to information, and in terms of the old medical language around transness, I was the “bad kind” who shouldn't be allowed to transition. That was incredibly discouraging. I met trans sex workers very young, and I thought “I would not survive that.” There was cowardice involved, as well. Also, before anything else, I'm a writer, and I had ambition, so a lot of things in my life, not just this, came in second place to that for a long time. I had to find a way to make myself employable to support a writing habit for 40 years. I have no regrets about that.

what are you reading?

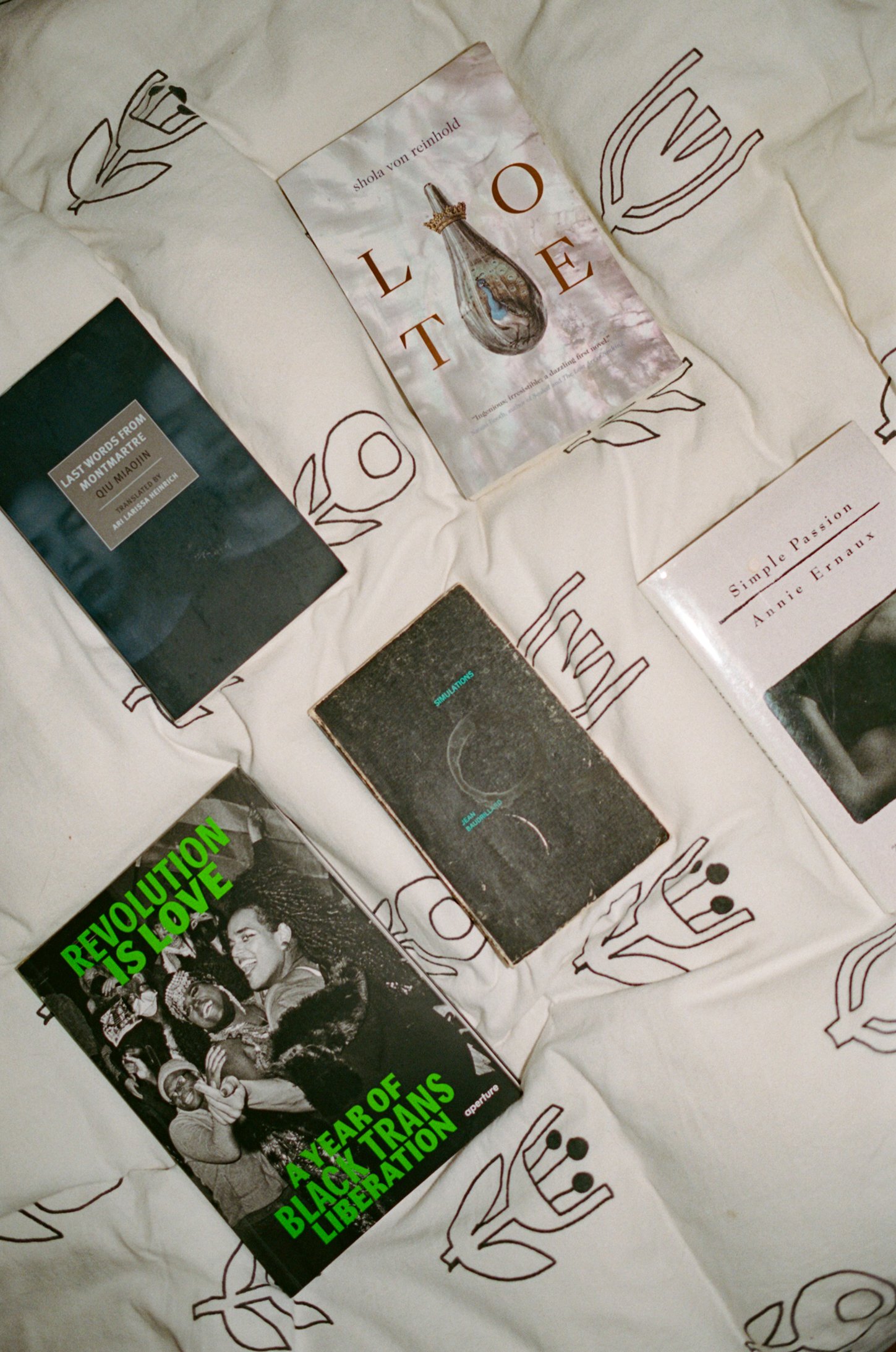

I’m currently reading Ian Penman’s book on Fassbinder, but if I can give anything a signal boost, it would be Shola von Reinhold’s Lote. Shola is a frighteningly young, Black, trans woman from the UK who lives in Glasgow, and this was her first book. It's a novel that creates an Afro-European, trans-queer-femme aesthetic, and in the process touches upon a lot of categories of Western aesthetics. It's also like a weird mystery story, we end up in an art residency that's this super white, European, high-concept nonsense, and this character has to unpack a mystery about the hidden Afro-European, Black Modernism threads in the background. Also in my current stack: Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard, Last Words from Montmartre by Qiu Miaojin, Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux, and Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation by Qween Jean, Joela Rivera, Mikelle Street, and Raquel Willis.

on her personal style

It all traces back to the Mary Quant era. I idolized my older sister and she came of age around little skirts with tights, big eyeliner, bright colors, and geometric patterns, I like all of that. I collect a lot of clothing that’s cheap shit, but I keep “disposable” pieces going for years. This is New York and everything gets covered in schmutz, so I keep things low-budget. I have this skirt that says ”offline” in English and Japanese that I've worn for, like, five years, but it's actually been two different skirts because I wore one out and bought another one twice. I love vintage Stephen Sprouse. He worked with Teri Toye, who was the first out trans model in the business — she was his muse, so not surprisingly, all that stuff fits me!

When I was cosplaying masculinity, I couldn’t find anything that worked, style-wise. I had a fucking hip hop tracksuit era, which was really embarrassing, and I always liked tight jeans for some reason. As I got older, I ventured into the whole suit thing for a while, but that gives you this ridiculous dry-cleaning overhead. So, nothing worked. Like a lot of trans women, the stuff I did really early on in my transition is really embarrassing and was way too slutty. That had to be wound down to what I'm comfortable in every day.

mckenzie’s favorite spots in nyc

I love dancing at Bossa Nova Civic Club and getting a coffee while browsing the excellent selection of books at Molasses. P&T Knitwear Books and Podcasts has lots of good space for working or meeting people.

interview and images by clémence polès, edited by em seely-katz