Philosopher and professor Elsa Dorlin has devoted most of her career to exploring the relations between violence, gender, and race, which she brought to the old-fashioned philosophy department of the Sorbonne, winning awards on the way. Her book ‘Self-Defense: A Philosophy of Violence’ was recently released in English by Verso: an important step in spreading her feminist approach of the importance of the body in everyday and political struggles. When she is not teaching in Toulouse or working at her home, Elsa can usually be spotted sleeping or grading papers on a train (her preferred mode of travel) or at flea markets. Below, she talks to us about her political background, and anti-capitalist commitment which she considers the most fundamental political question of our times, and the issue with contemporary feminism.

♫ Listen to elsa’s playlist | ⌨ elsa’s last google search

on her morning routine

My mornings are pretty much a state of permanent rush and chaos – a surrendering to stress. My routine is about getting used to stress, being late, and making sure I wake up the kids and get them to school. Everything has to be ready for me to have at least one sip of coffee. Either I blame myself by thinking I'm really not good at it, or if I reflect on our overall living conditions, in our daily lives, I understand above all that we are more or less all subject to unlivable rhythms of life. We are subject to too many injunctions, too much attention, and responsiveness, and the requirement for productivity, and so I tell myself that my "morning routine" is instead to sabotage the ideal of perfection and success somewhat, to carry out everything head-on, doing everything "correctly". The best thing in the morning is not to feel guilty.

on her upbringing and early political influences

When I was little, I wanted to be a poet. There was a lot of poetry at home growing up. Even my name is in reference to the poet Louis Aragon and to Elsa Triolet. I was really nourished by the poetry of Jacques Prévert, Andrée Chedid, Fernando Pessoa, and all francophone poetry, of course, especially the French Guianese poet, Léon-Gontran Damas. Our library at home also had the complete works of Karl Marx and a book by Foucault that I still remember called The Order of Things. I think we also had the autobiography of Angela Davis. It was an ideal library even though my parents did not have a higher education.

My mom’s whole family were communists, and my grandparents were members of the Resistance during the Second World War. On my father’s side, they are all from Guyana and were former slaves who found gold and became one of the main legacy families of Cayenne. That allowed them to send their kids to study in France. My great-grandfather was one of the first black automobile engineers in France.

““I did a lot of sports when I was younger and loved it. Handball, women’s gymnastics, fencing, swimming, Taekwondo… I eventually wanted to compete professionally or teach. The turning point was that I just didn’t have the level to compete. So I hesitated between literature, the humanities, and sports. In my senior year, I had my first philosophy class. I loved the way our teacher made us discover questions and corpora and was obsessed with each new question and author. That experience really pushed me to study philosophy in college.””

on what sparked her interest in research

I was very conscious that philosophy wasn’t going to pay the bills. I thought I was going to do it for a year, but I kept adding another year and another. And then I discovered research. I was completely fascinated by it — not so much by what we were taught at the university, but rather by all the philosophers who we weren't exposed to. What interested me was finding the forgotten philosophers. My first research was on women philosophers in the 17th century, who wrote treatises defending sex equality. And from there I knew this is what I wanted to do.

on her thesis and The matrix of race

I turned my thesis into a book called The Matrix of Race where I worked on the history of the emergence of categories of sex and race in the 17th and 18th centuries… the first conceptualizations of sexism and racism in modernity. A lot of it came from the history of medicine. In fact, my entire corpus is philosophers, naturalists, and doctors. I focus on the aftermath of the great witch hunt and the massacre of matrons and midwives. On the establishment of a medical apparatus essentially made of men who have access to the female body, and who define what it is, what it suffers from, and above all how to control its sexuality. From there, a definition of the antagonism emerges: man/woman, feminine/masculine, which will be anchored in the bodies. And simultaneously, when colonial medicine is set up, a part of medical thought ends up establishing racial categorizations to justify the natural inferiority of the enslaved people. Working on sex, race, and nation in philosophy in early 2000s France… no one was really doing that, especially while referencing feminist thought on the concept of gender, sexuality, race, and color.

““Being a philosopher in 2022 means above all being a teacher, a researcher, and rediscovering, recomposing, enriching, and sharing new libraries. Maybe we are all a bit of a philosopher, in the sense that we are more alive if we cultivate our curiosity, our desire to understand, to learn, but also to be, to change the world. Philosophizing is my job, it’s also a commitment: I have to situate my subject, explain my relationship to the world, and also oppose ideas that ignore or fuel injustice. Corpora and works have enlightened me, even liberated me, and made me what I am. In this sense, I admire the thought and commitment of the philosopher Judith Butler. Knowledge is not neutral, it is not outside the world and power relations, it is its effect, its reflection, but it is also a weapon, a resource at the heart of social struggles and emancipation movements.””

on how reproductive labor affects academic work

Writing and theoretical work requires long time slots, which require a form of tranquility, and an absolute de-responsibility of care. What’s complicated with the issue of reproductive labor is all the care involved. To write a book, you can’t think of what you’re going to eat for dinner, that you’re picking up your son from school, wake him up in the morning, or make sure his school bag is filled the way it should be. That’s why, when you think of a philosopher or an academic or a thought leader, you think of a man from a certain social class who has the means to delegate the work of reproduction to someone else, or to several people (usually women): you don’t think of a single mother! Nowadays, even women in academia often have the economic capacity or belong to a certain class that gives them the means to pay another woman to do part of the reproductive work. It’s not the case for me, for political and economical reasons. That’s why writing takes me longer, and why my books stay connected to the real world.

on how physical fight is related to gender

“To unlearn not to fight” is an idea that I elaborate on in Self-Defense: A Philosophy of Violence. It really tackles gender norms, how they are engrained and how they determine a socialization of the body. It’s the whole question of heteronormativity. It allows us to understand that to be raised as a woman is to be raised in a way that deprives us of every opportunity to experiment with our muscular body or to experience different forms of physical conflicts and contacts where we have agency. It’s not that we do not know how to fight because we haven’t learned it, it’s that we are taught to not do it. There is a history of women's self-defense, of feminist self-defense workshops and trainings. What we learn there is to defend ourselves physically, but also to break and undo what disciplines us, what encloses us, and forbids us to fight. When I’m scared of something, my first physical reaction is often to start shaking or be breathless. I’m going to interpret this as a weakness because I learned to not fight. Instead, I can read it as a signal to find safety and do something to protect myself. Pointing out these reflexes was very important to me. To make yourself small, to avoid, to flee can be the best self-defense techniques. We often take this as a form of not rising to the challenge, but in fact we are! We are just defending ourselves!

““I’m raising her within a philosophical and feminist framework, grounded in self-love and with foundations that make her distance herself from the way others look at her. I think especially when you’re a little girl, the gaze of others can be extremely intrusive. It can take up a lot of space and be really damaging, especially in the way we inhabit our bodies. I really want to be present for her so she inhabit her body in the most peaceful and powerful way. When I say power, it’s really about childhood and about the capacity to act the way she wants in her body.””

on contemporary feminism

Anti-capitalism is becoming the spearhead of feminism. Thanks to the Argentinian-Chilean movement, the needle is really moving, including in the US and Western Europe. A large part of the feminist movement was about being recognized and getting access to the same jobs without any obstacles. Since then, there has been a return to a library and corpus that is based more on black and brown feminism and on anti-capitalism struggles — a return and renewal to this forgotten memory that already constitutes a very strong force. If the claim of the feminist movement is to break the glass ceiling, we will still have to ask ourselves who is going to pick up the pieces. The ones that tend to pick up the pieces and clean our mess are poor women of color. To quote Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser, our feminism is not that of a white elite but that of the 99%.

If feminism only becomes an ad slogan for white, wealthy women, it won’t work. This is where we are now. In reality, it’s from here that things need to be repositioned, including questions of ecocide, the work of eco-feminism, and the whole anti-capitalist tradition in black feminism that’s been around for a long time. If we start to think, theoretically and politically, about feminism being attacked by neoliberalism, by police violence, and the patriarchal system, it would do every women, everyone, a lot of good. And it could save potential lives. It could save the world. There is no other way. It’s the only stance for every movement that fights patriarchy, heteronormativity, capitalism, racism, and climate change. We always have to think about who washes our socks, and at the end of the production line, who makes those socks. In which factory and under which working conditions?

““‘Who takes care of you?’ is in fact the most fundamental political question of our times. Taking care of yourself is crucial and means granting yourself moments of joy and pleasure. Thankfully, we can find these moments in times of extreme business. But around this idea of self-care is also the idea of who really is taking care of us. The chain of dependency is massive, it’s a question of economical politics. I think about it in terms of who works to make me live and and who depends on me to do the same.”

”

on the passerby who left a lasting impression

A couple of years ago, for my commute leaving work, I would take this Parisian metro line that gets nicknamed the “cattle truck”, which says a lot about the travel conditions. I made many encounters on it. There can be a lot of aggression between the travelers as the conditions can be unbearable, but, I particularly remember an encounter with an older woman… I had crossed the gaze of this woman, who most certainly was traveling for work, when I was going home. I had left her my seat, and we gave each other looks of encouragement, she thanked me and said to me by way of goodbye “go find your own and love one another” It was a dialogue between women — maybe mothers, or just community caregivers! — in a world of brutes… it was an affectionate attention, a feminist kinship, a gesture of recognition. That was it, but it stayed with me.

on her favorite books

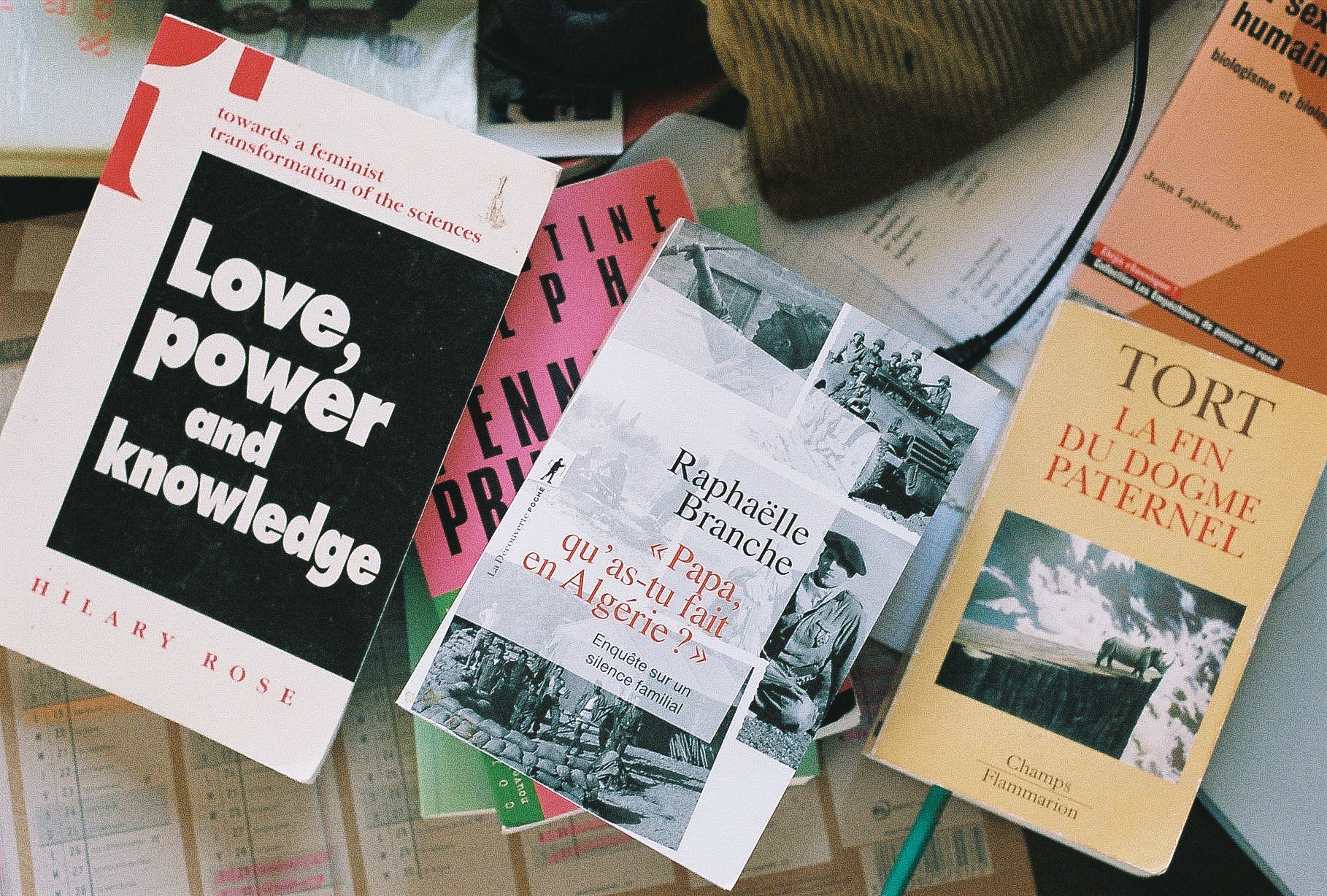

Within the classics, you have Love, Power and Knowledge by Hilary Rose, who is one of the most important feminist thinkers for me. She was the one who made us understand that the material conditions of existence and the question of care labor, and of domestic labor, have been instrumental in shaping new world visions and other concepts. After that, you have What did you do in Algeria? by Raphaëlle Branche, a remarkable French historian who specialized in colonial Algeria. It’s a very beautiful book on a way of writing history of war and colonialism and violence through the prism of family and transmission. I would also add I Tituba, Black Witch of Salem by Maryse Condé. For poetry, it would be June Jordan who I love. Also Black Skin, White Masks by Frantz Fanon and Feminist International by Veronica Gago. My most formative book was Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison.

on self-care, well-being routines, and rituals

We already know that well-being and happiness are first and foremost a market. So the question of what I can do in what amount of time and with what activity or products that could be beneficial is complicated. I find that this care, as thought of in a society of consumption when we talk about what I do and buy, is a very neoliberal understanding of happiness. But I also understand that these routines are important for some. I don’t want to create a hierarchy between things, but if we really want to think of well-being, I think we need to think about refusing this high-speed way of life, which is the injunction to work, to be efficient, to be able to lead family, love, affective, and professional lives. It’s to refuse all of that, including the concepts of paying attention to your body, your wrinkles, and what you’re eating. Instead, the focus has to be on slowing down, on refusal, and on exiting markets. For me, as my work never stops, refusal is a good ritual, a moment to refuse certain things like responding to emails at night or during weekends.

on her idea of beauty and how it’s changed over the years

Beauty and desire, particularly for women, can be a weapon, a resource, a protection, a form of self-defense, and a "privilege"... because of the dominant norms, the injunction to respond to the obligatory aesthetic of heterosexuality, to overconsume the toxic products of a lucrative market (cosmetics, fast-fashion, but also well-being, food, decoration, etc.) that transform our bodies, our homes, our lifestyles, into commercials. These norms are socially and historically those of a patriarchal and racialized capitalist system. It is difficult to detach from this system because it affects self-esteem, our need for recognition, and the desire to be loved. Beauty and desire, love and recognition are political, that is to say, they must be politicized: it is not only a question here of affirming "one must love oneself". Depending on age, disability, skin color, or hair texture, depending on class, you become or are socially less "lovable". However, we battle every day, in our daily life, in our intimacy, to build ties that make us better, and more powerful... At 48, I don't care if I feel beautiful or not; I want to feel good, I want to feel right, in agreement with my choices, and my hopes, to take care of my own and, to the extent of my abilities and my history, of myself.

images and interview by clémence polès