Camera Roll is an interview series where we glimpse into the current moment via the mundane and the ordinary — the life documented and forgotten, lived through our phones and beyond.

A third-year student studying art and film in London, Niki Kohandel can routinely be found across the UCL campus editing films, making prints, or passing the time outside with friends. When not doing those things, she's "most likely spotting swans" on the banks of St James's Park Lake. "My fascination for them started last year, after meeting a woman in Paris who goes to the same park bench every day to feed a black swan," recounts Kohandel. Impulses to meditate on what makes the quotidian details of life remarkable like this appear in her work — an impressive body that includes two short films, The Sparrow is free and Just another year, both of which both draw upon her familial relationships and French and Iranian heritages. Continuing reading for Niki's notes on what it's like editing and rehashing the sometimes painful past, how homesickness sparked her early work, and which Chantal Akerman film gets her out of bed each day.

Where are you right now?

I live in London. I’m studying at the Slade, which is the art school within UCL.

what kind of phone do you have and how many images do you have in your camera roll?

An iPhone with a screen cover that doesn't let anyone spy over my shoulder on the tube. With 12,562 photos and 585 videos on it.

What’s your morning routine?

That really depends on what happened the night before! But I usually wake up early, around 6am or 7am, and don't do much for about an hour. There's a spider that is knitting its web right outside of my window, and on days when I see it, I like to think we're saying good morning to each other. I try to catch up on readings, and sometimes I watch a short or a movie if I have time because I'm less likely to fall asleep than if I did it in the evening. Then, I'm reminded of Chantal Akerman's words in her short film 'Portrait of a Lazy Woman': "to make cinema, one has to get out of bed," so I get out of bed.

Tell us a little bit about your background and journey.

I was born in Paris, and although both my parents are Iranian, I always spoke Farsi with my mom and French with my dad. What I mostly remember is the time spent with my grandmother: feeding pigeons, sewing lots of fabric bits together, and believing her house was a palace just because it was in the suburbs and had a garden.

We moved to Brussels when I was 7, expecting to come back after two years. I was 14 when I returned to France with my mother, this time to Toulouse, where not much was happening. She and I spent a lot of time watching crime shows and going to the movies every weekend with my uncle.

how did you first get into film?

Growing up, I was a nerd who was convinced she wanted to become a fashion designer. It was only when I arrived in London that I realized it wasn't my thing. I took the art route instead: I started on a painting pathway at Central Saint-Martins, but I don't think I held a brush for more than a week in that course. Ever since I was little, I had always been drawing, but being in a room with fifty other students who already knew how to stretch a canvas and paint with oil made me very self-conscious about anything I would do. Fortunately, we were encouraged to think about the medium in other ways too, which is why I started experimenting with moving images.

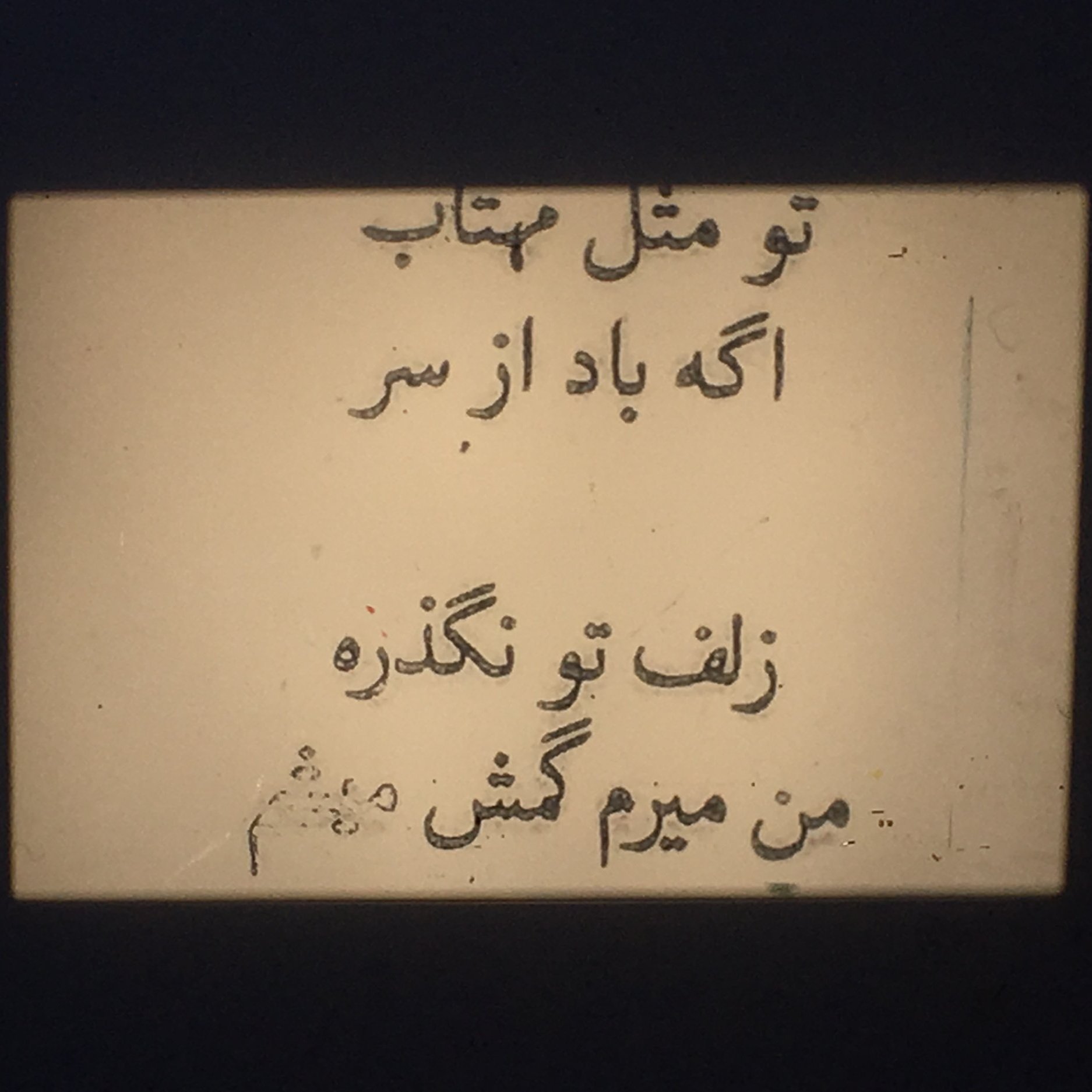

I was probably homesick when I started listening to Gol-e-goldoone man, an Iranian song I've always heard my mom hum growing up. The lyrics are intensely sad — the singer asks about a flower which has broken in its vase — and I started layering them with other images, mostly archives from my family's life in the 70s and 80s in Iran. At first, I was using an overhead projector, and a few months later, I began working with editing software for the first time. That was also when I began watching arthouse films — Chantal Akerman, Marguerite Duras, and Sergei Parajanov are amongst my favorites.

When I look back now, that decision makes a lot of sense; you'll see me reach for the camera in all the footage my mother has taken of me since I was 1.

what do your days look like?

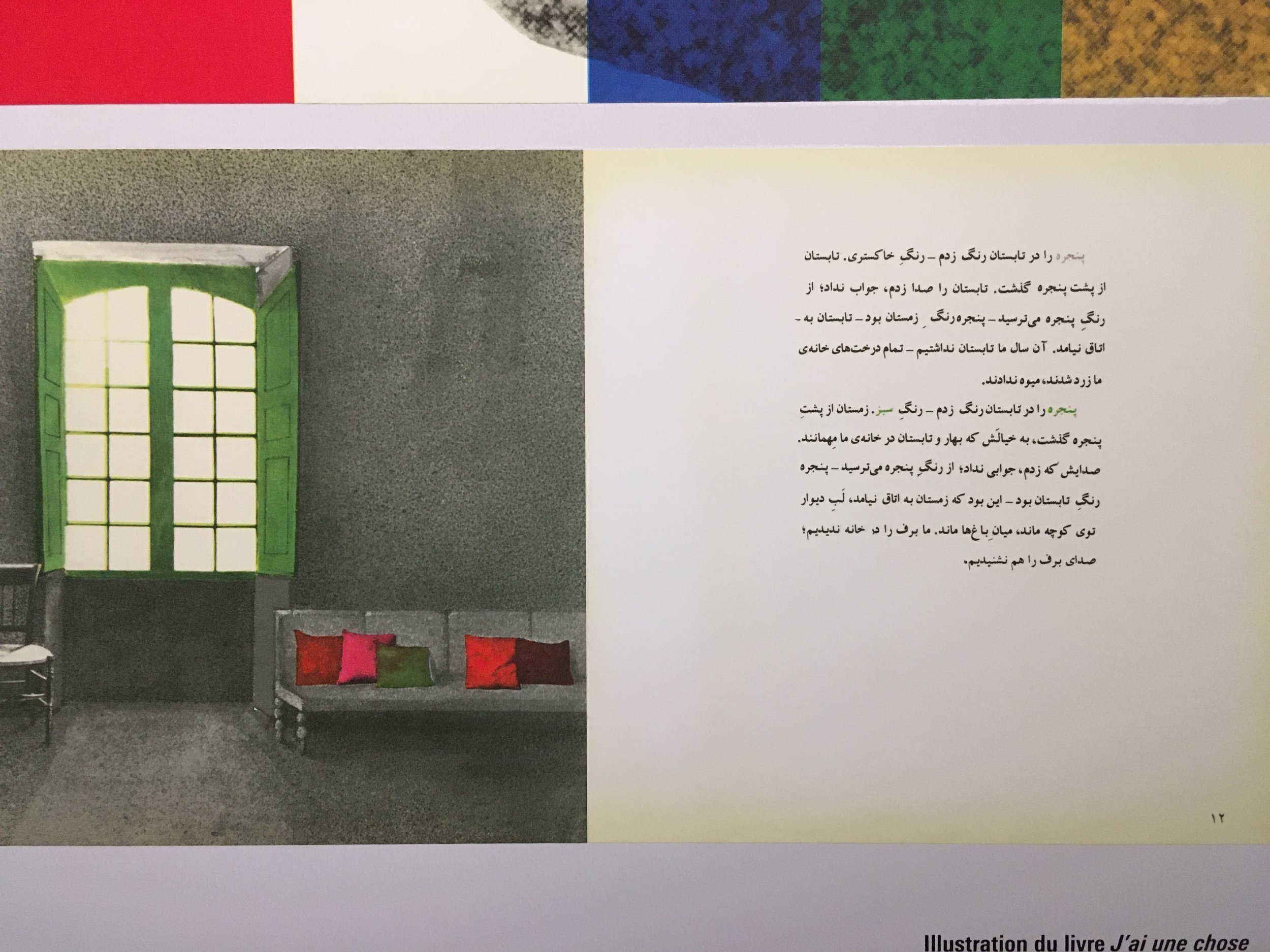

This year, most of my work has been producing books and films for Shahre Farang, an initiative I started with my friends to provide creative care in bridging hotels, where children and their parents who have recently arrived in the UK are staying. Although I'm on the art side, which includes writing stories and mono-printing to illustrate them, my days also involve a lot of Zoom meetings and emails.

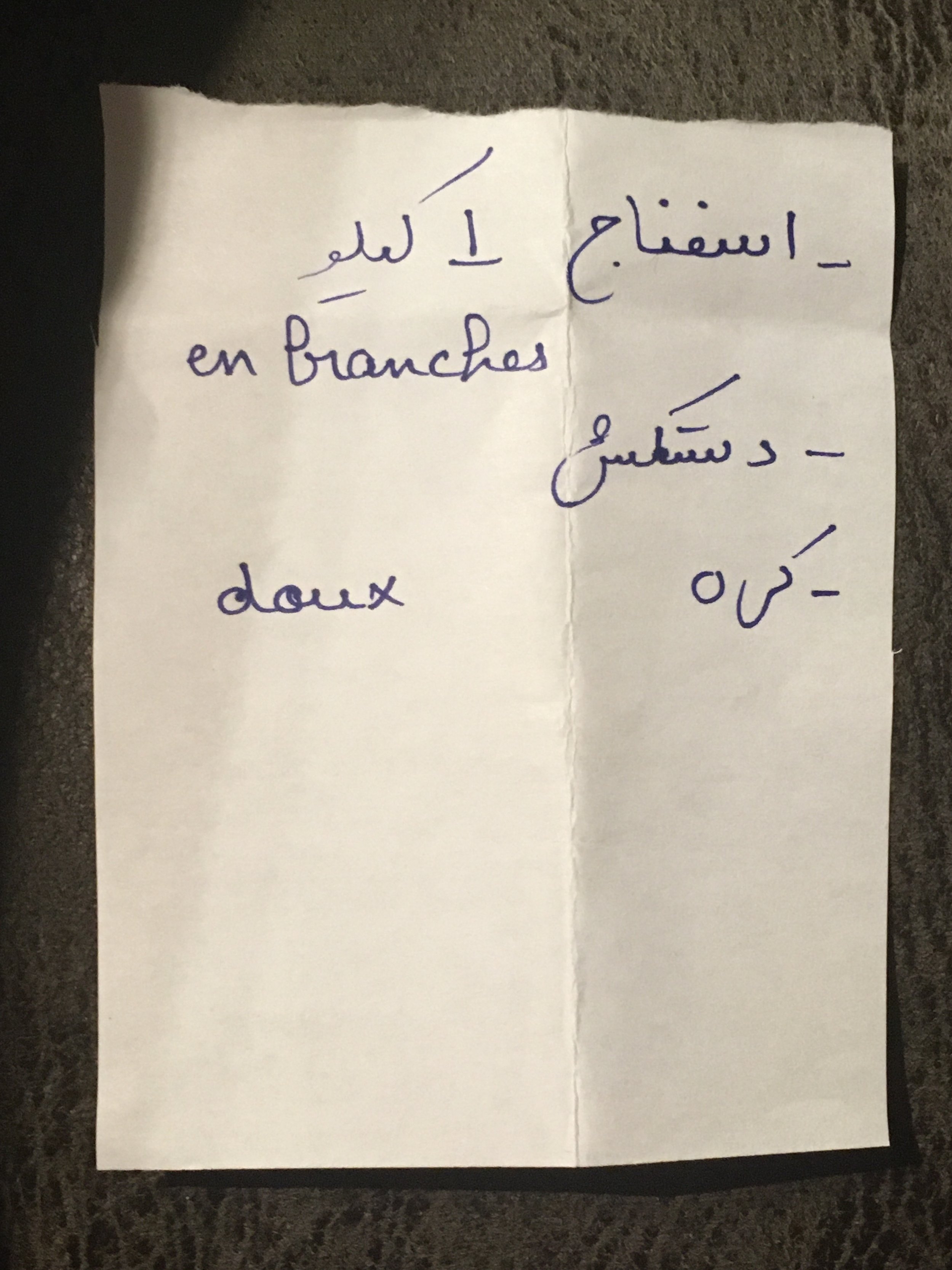

I'm also working on other films. None of them fit into the documentary/fiction binary, but all are concerned with how we communicate and translate one another's stories. I'm interested in the gaps that occur in those exchanges: even when we speak the same language, they exist but aren't necessarily noticed, so revealing them is what I attempt to do. I got my father to translate the last story I wrote in Farsi into braille, which also meant translating those words into light — he literally punched the letters onto 16mm film. Once projected, this created something that was very close to seeing moon phases or stars.

how do you strike a balance between work and your personal life?

It's pretty difficult for me to separate my life from my work. Phone calls with my family often turn into proofreading sessions, where I ask my parents or aunt to check for grammar and spelling mistakes in my writing in Farsi. My flatmates are also involved in Shahre Farang: we needed help on the admin side, and they are the most organized people I've ever met. One of them couldn't have her sister (with whom I started the project) over without me hijacking her visit into a work meeting. I'm nowhere near reaching a balance, so I'm unfortunately the last person one should go to for advice!

Your work feels so personal; it examines a lot of your own family's history, anecdotes, and traditions. How do you decide what to include and what to keep private?

Editing is time-consuming, and it often means rehashing the past, and whether that's my own or someone else's, it can be draining, even painful at times. But it's rewarding to do it myself, and it's ultimately the way I remain in control. That, and constantly talking with those involved in the filmmaking process, dictates how much I reveal from a story. The idea for The Sparrow is free came to me when I found recordings of my grandmother on my phone. In them, she had told me about her wedding at the age of 17 and her divorce at 40, the latter of which was the best day of her life. At first, my dad was quite reluctant about me showing this film outside of school. He argued that she might not remember what she had said at the time and wouldn't want so many personal anecdotes about her marriage made public. But it is her story, and I made sure that she was aware of everything she had disclosed back then. She's more than happy to know it is shared with others now. Time and distance are incredibly useful when it comes to sharing the difficult moments one has experienced.

what excites you most about the filmmaking world, and what do you most wish you could help change?

The breaking down of boundaries between what can be shown in a cinema and what is contained within the art sphere is very exciting. I hope that, in general, we can move towards fewer categorizations and more interest in crossing genres. It's great to be able to enjoy a documentary or a rom-com for what it is, but I do believe it's important for audiences to be surprised and for filmmakers not to be limited by codes, which can at times be a means of gate-keeping for the industry.

any advice for those with aspirations to get into your line of work?

Don't get too stuck on how you think it should be made or should look. I never thought I would end up making films, just because the idea I had of them was completely informed and defined by what I saw growing up — a lot of TV shows and mainstream movies, which are always produced with crews and budgets. Later, I understood that film is essentially about people telling a story together, which made it sound less daunting and inaccessible. Of course, if you break filmmaking down into components, you'll quickly realize you can't do it all perfectly by yourself. But it is about working around the things you can't do and doing something in spite of that.

When was the last time you did something you’d never done before?

Last January, when I sat in Cinema 1 at the ICA to watch my film The Sparrow is free being screened for London Short Film Festival; the first time I saw it on a big screen. I was very lucky to have some of my friends in the audience because I felt quite nervous showing it to people I didn't know!

are there any places or organizations you're supporting or wish you could support?

I've been meaning to attend one of Migrateful's cooking classes for ages. Refugees and migrants in the UK lead their sessions, and I finally managed to sign up for a volunteering shift. I'm very excited to help a chef prepare sabzi polo bâ mâhi (rice, herbs, and fish) — a dish that Iranians traditionally have for Norooz.

what’s been inspiring you?

Abbas Kiarostami's illustrations for I've Got Something to Say that Only You Children Would Believe, a street lamp that fell in Bloomsbury, the carpet that has seen me grow up, Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet, and tea with a really good friend.

What’s your favorite gear you shoot with?

I mostly shoot with the Hi-8 camera that my mother received as a gift from my father when I was born. She recorded my childhood on more than 20 mini-DV tapes, and nearly ten years later, the roles have reversed — though I'm still far from capturing the countless hours of recordings she has of me!

I love shooting analog, but only very recently got over my fear of filming with a Bolex or on 8mm: I had bought one Super 8 cartridge during my first year at the Slade and only used it last September. For a long time, the financial cost of the process made it feel extremely precious. I wouldn't allow myself to be as spontaneous as artists who used the medium back when it was first democratized and much cheaper.

how do you use your phone or other tools to mark and remember your life?

I have very ambivalent feelings when it comes to capturing moments of my life with my phone because the format feels too tied in with social media. Yet it's also one of the most efficient ways by which I can document my life and share the things I make with my close ones. I wouldn't be able to move forward with my writing process as quickly if I had to rely on sending letters and photographs via post. I try to always have at least one recording tool with me, even if it's just a notebook and a pen, but I'm not strict with it. It's freeing to be forced to live in the moment, and I don't believe that you're meant to record and remember everything in your life; it's a debate I constantly have with my family members, who have quite a different take on that.

I'm not very methodical, and I haven't found a system that brings all these recorded fragments together. I watched Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige's Memory Box a few months ago, which made me think of what mine could look like: unlabelled film negatives, notebooks full of illegible scribbles that combine French and English with childish Farsi handwriting, and drawings, always of the same character — a little doll drawn that appears across most of the stories I write. I'm unsure of whether it would make a lot of sense to someone who would find those in twenty years!

what style do you like to use when taking photos and videos on your phone?

I'm quite spontaneous when it comes to taking photos or filming with my phone, so my camera roll is full of random shots; it doesn't actually look as curated as this! I'm not very good at making the most out of available lighting either, so the one rule I have for taking photos of myself is to use a flash or not take the photo at all.

How long do you typically spend on your phone in a day?

More than I would like to admit to myself. I got tired of seeing those notifications about the average time I spend on it, so I disabled my Instagram for a couple of weeks, and that drastically cut it down to around an hour per day.

last thing you googled on your phone?

The last thing I googled was ‘à l’enseigne de la fille sans coeur.’

Favorite thing you’ve come to possess in the past year?

Actually, a present I received from my mother after moving to the flat I'm currently living in: a carpet from Treasure Land on Holloway Road.

What are you reading?

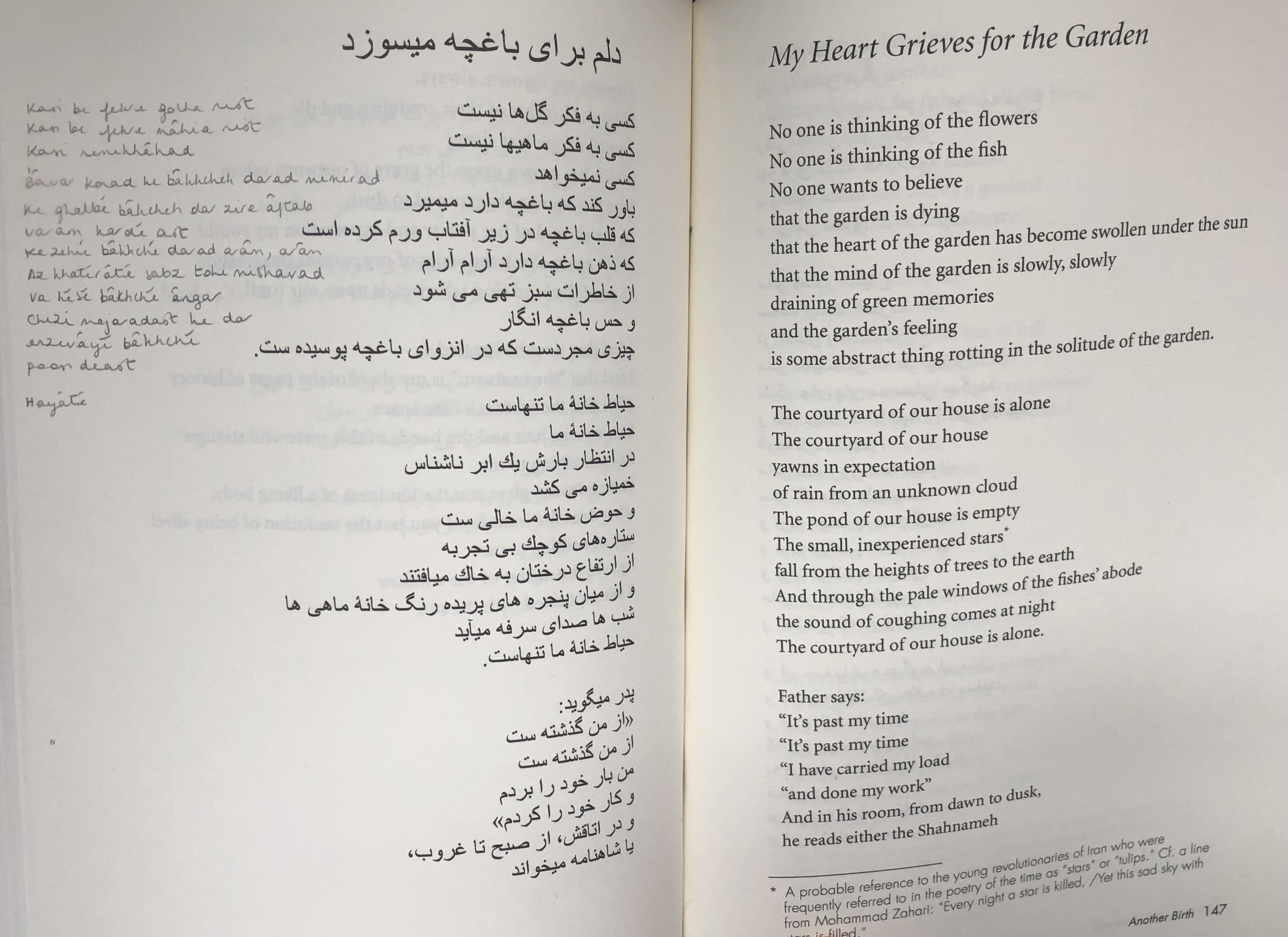

Forrough Farrokhzad's poems, Azita Ghahreman’s Negative of a Group Photograph, short stories by Zoya Pirzad, David Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous, and Paul Auster's collection of essays, The Art of Hunger.

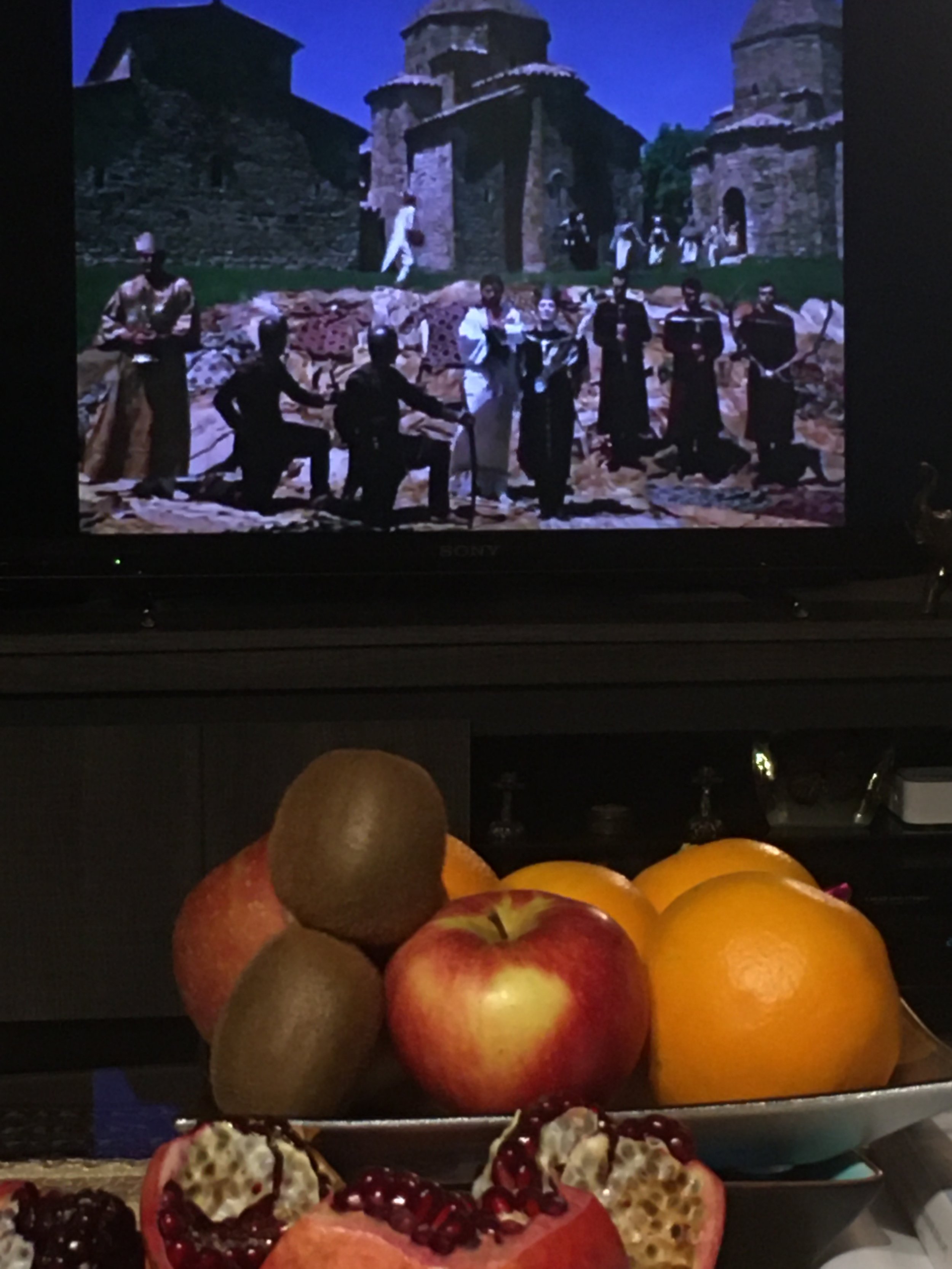

What are you watching?

I Like Life a Lot, an animation made in the ‘70s by Roma children and their teacher Kati Macskássy in Hungary, Petite Maman by Céline Sciamma, and My Life as a Zucchini by Claude Barras.

images provided by niki kohandel, interview by marina sulmona